Kef music is the Armenian‑American social dance and party tradition that grew in immigrant communities, especially on the U.S. East and West Coasts. The word “kef” (քեֆ) means festivity or good mood, and the music is made for weddings, communal gatherings, and long dance sets.

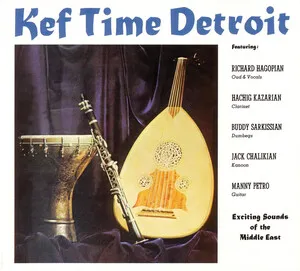

It blends Armenian and broader Ottoman/Anatolian folk repertories with the instrumentation, swing feel, and band format that Armenian, Greek, Turkish, Assyrian, and Arab musicians encountered in the United States. Typical ensembles feature oud, clarinet or saxophone, violin, dumbek (darbuka), riq, and often drum set, bass, accordion, guitar, or kanun. Melodies are makam‑based, ornamented, and heterophonic; rhythms favor dance meters such as 6/8, 9/8 (karsilama), 7/8, and 4/4.

Repertoire includes line and circle dances (e.g., kochari, shoror, bar, tamzara), improvisatory taksim introductions, and songs in Western Armenian dialect. Sets are arranged to keep dancers moving, often medleying tunes and alternating instrumental and vocal numbers.

Armenian immigrants arriving in the United States in the 1910s–1930s brought village dance tunes, Ottoman‑Armenian café music, and sacred/secular song. In urban enclaves (New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Detroit, Fresno), musicians performed in cafés and social halls where mixed Armenian, Greek, Turkish, Assyrian, and Arab audiences gathered. The term “kef” came to denote these convivial parties and the music played for them, characterized by makam‑based melodies, taksim (improvised preludes), and driving dance rhythms adapted to longer, American‑style social sets.

By the 1940s–1960s, Armenian‑American dance bands crystallized the kef sound. Groups such as the Vosbikian Band popularized brass/woodwind‑forward arrangements (clarinet, sax) alongside oud and percussion, absorbing swing and big‑band tightness while retaining Anatolian rhythmic cycles (6/8, 9/8, 7/8). Wedding circuits and community clubs sustained a vibrant scene; repertoire standardized around kochari, shoror, bar, tamzara, and regional songs sung in Western Armenian.

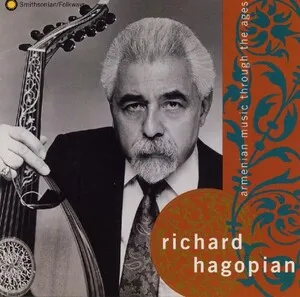

From the 1960s–1970s, artists like John Berberian, Richard Hagopian, Onnik Dinkjian, George Mgrdichian, and Souren Baronian recorded influential albums. Some releases kept a traditional dance focus (“kef time”), while others experimented—bringing in drum set, electric bass, and jazz/rock colors—without abandoning modal language and asymmetric meters. These recordings circulated beyond Armenian circles, intersecting with the U.S. belly‑dance community and world/jazz audiences.

Through the 1980s to the present, kef music has remained central to Armenian‑American social life, taught informally within families and formally in folk ensembles and university programs. Younger musicians have revived deep repertory and regional styles while updating arrangements and production. The genre continues to bridge tradition and cosmopolitanism, anchoring community identity on dance floors at weddings, picnics, and festivals.