Rebetiko is an urban Greek popular song tradition that crystallized in the port cities of Piraeus, Thessaloniki, and the broader Aegean world after the Asia Minor Catastrophe of 1922. It emerged among refugees and working-class communities, drawing on Ottoman/Turkish makam-based modal practice, Byzantine-liturgical melos, and Greek rural folk song (dimotika), then transforming these into a distinctly urban sound.

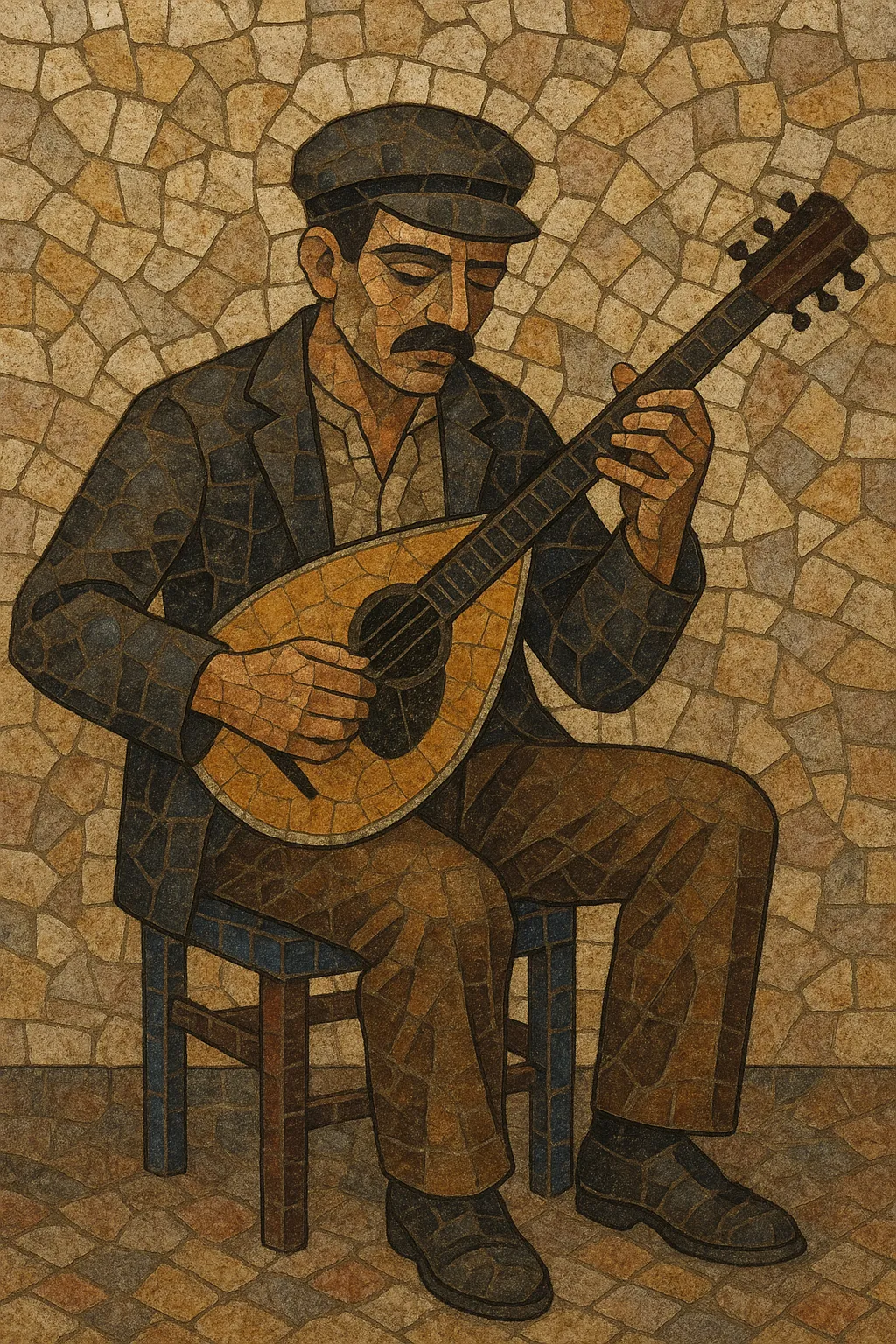

Typical rebetiko pieces are strophic songs led by bouzouki or baglamas, often prefaced by an improvised modal solo (taximi). Rhythms center on social dances such as zeibekiko (9/8, usually grouped 2+2+2+3), hasapiko (2/4 or 4/4), hasaposerviko (fast 2/4), karsilamas (9/8), and tsifteteli (4/4). Lyrical themes can be raw and direct—love, exile, poverty, prison life, hashish dens (teké), pride, and the ethos of the underworld (mánges)—frequently expressed with argot and melismatic vocal style.

Over time, rebetiko evolved from the Smyrna-style ensembles of oud, violin, and santouri to the Piraeus style centered on trichordo bouzouki, baglamas, and guitar, and later fed directly into the development of laïko and modern Greek popular music.

Rebetiko coalesced in the wake of the population exchanges of the early 1920s, when refugees from Asia Minor (especially Smyrna/İzmir) settled in Greek ports. These communities brought café-aman performance culture and makam-based song forms (amanes), blending them with Greek folk (dimotika) and Byzantine chant aesthetics. Early recordings feature ouds, violins, santouri, and female vocalists such as Roza Eskenazi, embodying the so‑called "Smyrna school" sound.

By the early-to-mid 1930s, a tougher, more stripped-down "Piraeus style" emerged, centered on trichordo bouzouki, baglamas, and guitar. Artists like Markos Vamvakaris, Giorgos Batis, and Anestis Delias codified a repertoire of zeibekika and hasapika with distinctive taximia (improvised introductions) and modal melodies (e.g., Hitzaz/Ḥijāz, Rast, Ussak). Lyrics often depicted the life of the manges, prisons, hashish dens (teké), and urban hardships.

The Metaxas dictatorship (from 1936) imposed censorship, curbing overt drug references and certain orientalizing elements. During WWII and the Occupation, rebetiko persisted as an expressive outlet, with major composers like Vassilis Tsitsanis shifting the style toward more refined lyrics and harmonies, setting the stage for postwar popularization.

After the war, rebetiko’s idiom broadened and professionalized in urban nightspots. Tsitsanis, Sotiria Bellou, and collaborators introduced more guitar- and bouzouki-led arrangements with clearer Westernized harmonies while retaining modal color, directly catalyzing the rise of laïko (urban Greek pop). The boundary between late rebetiko and early laïko became fluid.

In the 1960s–70s, a major revival (in scholarship, performance, and recordings) re-canonized classic rebetiko and its creators. Since then, the genre has been a foundational pillar of Greek musical identity, continually reinterpreted by contemporary artists, and studied globally for its synthesis of Eastern Mediterranean modal practice with modern urban song.