Persian music refers broadly to the musical traditions of Iran, centered on the radif repertoire and the modal system known as the dastgāh and its related āvāz branches.

It is characterized by microtonal intervals (koron and sori accidentals), fluid melodic development through short pieces called gusheh, and a performance practice that balances composition with refined improvisation (bedāheh-navāzi).

Typical ensembles feature tar, setar, kamancheh, santur, ney, and frame drums such as tombak and daf, with vocals employing the distinctive ornament called tahrir. Texts often draw on classical Persian poetry (Hafez, Rumi, Saadi), yielding contemplative, romantic, and introspective moods.

While the tradition’s roots reach back to pre-Islamic Persia, its courtly and urban forms crystallized from the Safavid era onward and were codified in the Qajar period, continuing to influence regional modal musics across West and Central Asia.

Persian musical culture traces to pre-Islamic Iran, notably the Sasanian court (3rd–7th centuries) where legendary figures like Bārbad are associated with organized modal practices and court repertoires. After the Islamic conquest, Persian musicians and theorists were central to the musical life of the Abbasid courts, helping shape the shared learned traditions of the region.

Between the 9th and 12th centuries, polymaths such as al-Fārābī and Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna) systematized concepts of intervals, modes, and rhythm. Persian and Arabic scholarly milieus influenced each other deeply, laying foundations for later maqām/dastgāh systems across West and Central Asia.

Under the Safavids (1501–1736), courtly and urban practice matured with lutes (tar/setar), spike-fiddle (kamancheh), and end-blown flute (ney). In the Qajar era (1789–1925), the radif—an ordered corpus of melodic types (gusheh) within dastgāh and āvāz—was transmitted by master performers and became the canonical backbone of classical performance. The radif’s structure encouraged both memorization and nuanced improvisation.

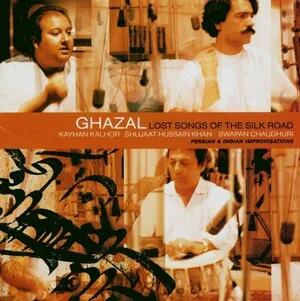

From late Qajar into Pahlavi Iran, masters such as A.H. Vaziri, Abolhasan Saba, and Ruhollah Khāleghi advanced pedagogy, notation, and orchestration, while radio and institutions popularized classical and light-classical forms (pīshdarāmad, chahārmezrāb, tasnif, reng). After 1979, the tradition continued through both domestic revival and a strong diaspora presence, with international collaborations bringing Persian instruments and modal aesthetics to global audiences.

Today, Persian music thrives in classical, folk, sacred, and popular contexts. Artists uphold the radif while exploring fusion with contemporary genres, and the dastgāh approach remains a reference point for neighboring modal traditions (e.g., mugham and shashmaqam), as well as for modern world, film, and cross-cultural projects.