South Asian music is a broad regional meta-genre that encompasses the diverse classical, devotional, folk, and popular traditions of the Indian subcontinent, including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, and the Maldives.

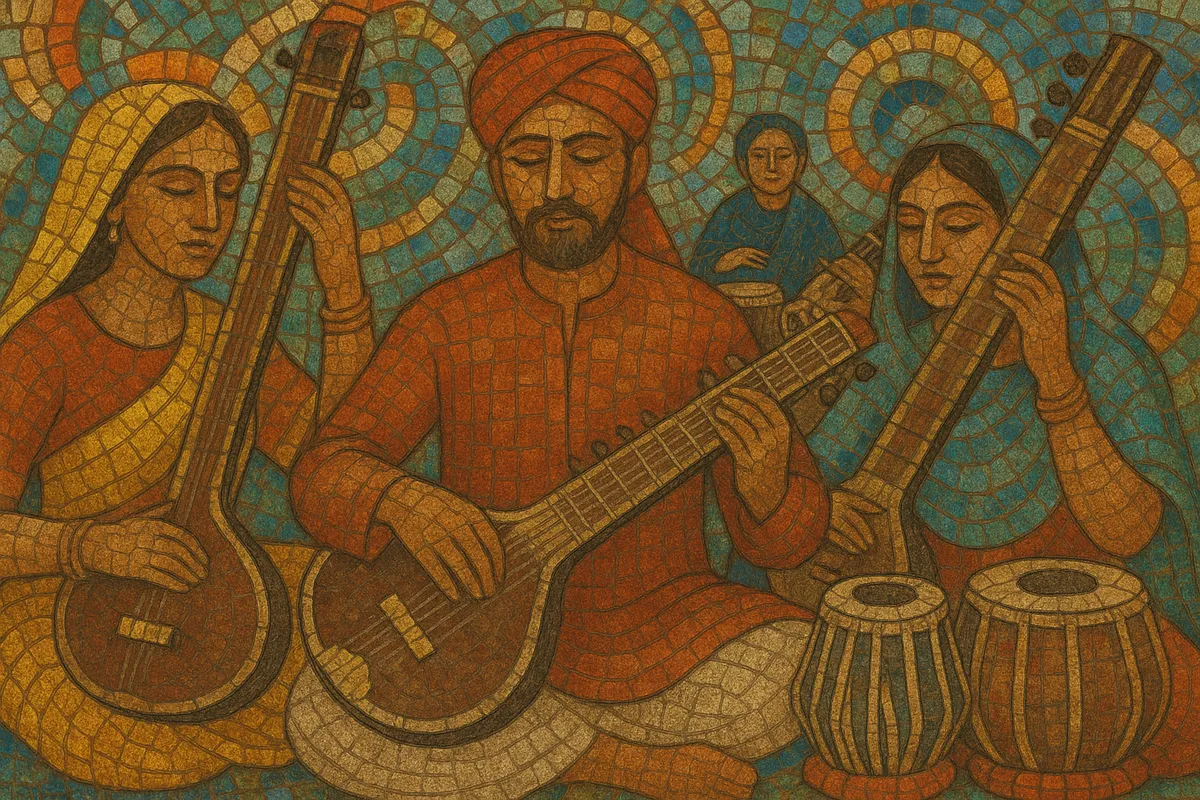

It is organized primarily around modal melody (raga/ragini systems and related regional modes), cyclical rhythm (tala and folk meters), and a strong emphasis on improvisation, ornamentation, and timbral nuance. A constant drone (often tanpura or shruti box) and intricate percussion languages (bols) are characteristic across many forms. Devotional currents (bhajan, kirtan, qawwali), courtly and Sufi lineages, and countless folk idioms feed into modern popular styles from filmi/Bollywood to regional pop and diaspora fusions.

While the roots reach back to ancient Vedic chant and early treatises, much of the classical grammar and performance practice recognizable today coalesced between the late medieval and early modern periods, shaped by temple, court, and Sufi contexts and later interfacing with colonial modernity and global pop.

South Asian music traces to ancient ritual and liturgical practices, especially Vedic chant, which established principles of pitch, intonation, and recitation. Over centuries, treatises codified modal ideas that would later inform raga thinking, while temple, folk, and court settings diversified performance roles.

Between the late medieval and early modern eras, the region’s classical languages took on recognizable shape. In the north, Hindustani music matured through courtly patronage and contact with Persianate culture, embracing khayal, dhrupad, and instrumental lineages. In the south, Carnatic music consolidated concert forms (kritis), pedagogies, and tala vocabularies in temple and court milieus. Devotional streams—bhakti singing, kirtan, and Sufi qawwali—flourished in parallel and often intersected with classical and folk practice.

Alongside elite courts and temples, every linguistic region nurtured folk idioms (e.g., Punjabi, Bengali, Rajasthani, Marathi, Tamil) with distinctive instruments, dance, and festival contexts. Devotional music—bhajan, kirtan, abhang, and qawwali—remained a primary channel for musical transmission, memory, and innovation, reinforcing call-and-response, communal participation, and poetic exchange.

Printing, gramophone records, radio, and cinema reframed patronage and audiences. Early film songs and theatre integrated classical, folk, and Western instruments, birthing a modern studio aesthetic. The microphone favored lighter, nuanced vocalism, while orchestration expanded harmonic color beyond the traditional drone-and-raga framework.

Post-independence cinemas (Bollywood and other regional industries) catalyzed a pan–South Asian popular repertoire. Diaspora communities helped globalize bhangra, filmi, and devotional fusions; the psychedelic and rock worlds embraced raga concepts (raga rock), while Goa’s party culture became central to trance lineages. Contemporary scenes span conservatory-classical to indie, hip hop, electronic, and hybrid devotional pop, all retaining strong ties to raga, tala, and text-centered poetics.