Turkish music is a broad umbrella encompassing the courtly classical traditions of the Ottoman era, regional folk styles of Anatolia and Thrace, Sufi devotional practices, and modern popular forms that blend local aesthetics with global genres.

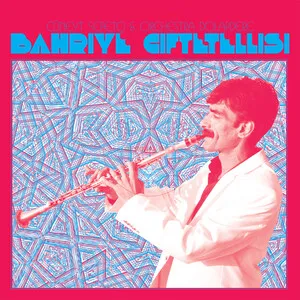

Its classical core is organized by makam (melodic modes) and usul (cyclical rhythms), using microtonal intervals and rich ornamentation. Instruments such as oud (ud), tanbur, ney, kanun, bağlama (saz), kemençe, and a variety of frame and goblet drums are central. Folk idioms feature asymmetrical meters (like 9/8 or 7/8), call‑and‑response vocals, and dance forms like halay and çiftetelli.

Since the 20th century, Turkish music has integrated Western harmony, orchestration, and production techniques, giving rise to arabesk, Anatolian rock, Turkish pop, and hip hop while maintaining the expressive depth and modal nuance characteristic of its older traditions.

Turkish music coalesced during the Ottoman period, drawing on older Central Asian Turkic melodies, Sufi practices, and the courtly traditions of the broader Eastern Mediterranean. By the 16th–18th centuries, Ottoman court music matured with formalized makam (modal) systems and usul (rhythmic cycles), cultivated in palaces, Mevlevi lodges (tekkes), and urban centers like Istanbul.

Composers such as Buhurizade Mustafa Itri and Hammamizade İsmail Dede Efendi advanced a refined repertoire of instrumental forms (peşrev, saz semaisi) and vocal genres (ilahi, beste, şarkı). Mevlevi ceremonies integrated music, poetry, and sema (whirling), while virtuosi like Tanburi Cemil Bey bridged classical and folk sensibilities, expanding technique and timbre.

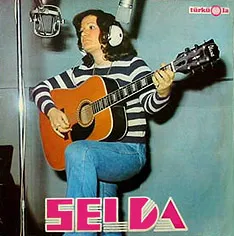

Following the founding of the Republic (1923), institutional reforms promoted Western musical education and notation while preserving classical and folk archives. Radio and recording industries popularized regional folk (türkü) and urban styles. Mid‑century stars like Zeki Müren defined a polished, orchestrated "classical" popular sound.

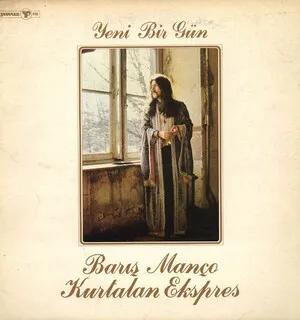

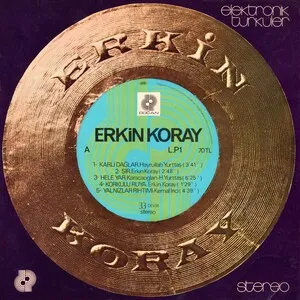

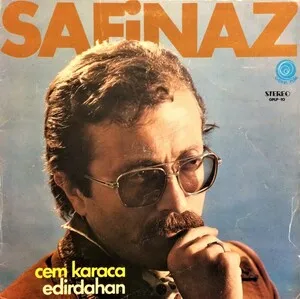

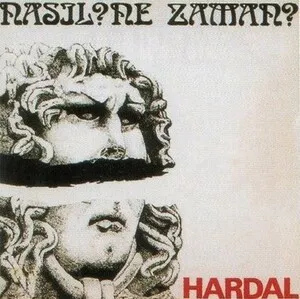

From the 1960s–80s, Anatolian rock merged makam ideas and asymmetrical rhythms with rock instrumentation (Barış Manço, Erkin Koray). Arabesk (Orhan Gencebay, Müslüm Gürses) channeled rural‑to‑urban longing through microtonal melodies and emotive lyrics. From the 1990s onward, Turkish pop (Sezen Aksu, Tarkan) and later hip hop integrated international production with Turkish melodic contours.

Today, Turkish music spans conservatory classical, regional folk revivals, Sufi‑inspired fusions, indie/rock, club music, and diasporic hip hop. Across these forms, the aesthetics of makam, expressive vocalism, and distinctive rhythms remain influential, even when reframed by Western harmony and modern studio practices.