Turkish folk music (Türk Halk Müziği) is the traditional, orally transmitted music of Anatolia and Thrace, shaped by centuries of village life, nomadic routes, and urban courtly exchange. It marries local poetic forms with the modal (makam) vocabulary common across the Eastern Mediterranean, and favors distinctive "aksak" (limping) meters.

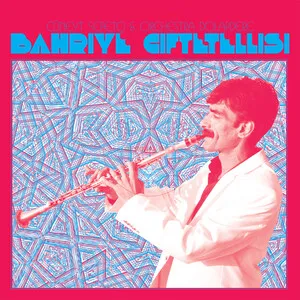

Core instruments include bağlama/saz (and its family: cura, divan sazı), kaval and ney (end-blown flutes), zurna (shawm) with davul (bass drum), kaşık (spoons), darbuka, kabak kemane (spike fiddle), regional kemençe and tulum (Black Sea), and clarinet (especially in Thrace). Vocals often feature heterophony and ornamentation, spanning two main tempo-types: "uzun hava" (non-metric, free-rhythm song) and "kırık hava" (metric, dance-oriented song). Well-known regional/dance forms include zeybek, halay, horon, semah, and çiftetelli.

Themes typically explore love and longing, migration and exile (gurbet), nature, social satire, and mystical devotion (Alevi-Bektaşi deyiş). The modern category coalesced in the early Republic through collection, notation, and broadcasting, yet it preserves strong local dialects and microtonal nuances.

Turkish folk music descends from the oral traditions of Anatolia and Thrace, with roots in Oghuz Turkic song, Central Asian itinerant bardism, and centuries of interaction with neighboring Greek, Armenian, Kurdish, Arabic, and Persian communities. The aşık/ozan (minstrel) tradition flourished from the 16th century onward, accompanying poetry on the saz and shaping forms such as koşma and deyiş. Village ensembles of zurna–davul provided music for rites of passage and community dances, while Black Sea strings (kemençe), Aegean zeybek styles, and Central Anatolian bozlak cries articulated strong regional identities.

Throughout the Ottoman period, folk repertories coexisted with Ottoman court/classical music. Shared modal thinking (makam) and rhythmic cycles (usul) enabled porous boundaries: folk melodies could be urbanized, while court idioms seeped into rural song. Sufi orders nurtured devotional genres (e.g., Alevi-Bektaşi semah and deyiş) that bridged mysticism and village life.

Following 1923, the new Republic invested in national culture-building. Field-recording teams and scholars (later amplified by Muzaffer Sarısözen’s work and TRT) collected, transcribed, and arranged thousands of türkü for radio. This period effectively codified "Türk Halk Müziği" as a national canon, standardizing instruments (notably bağlama), tunings, and performance practice for urban audiences.

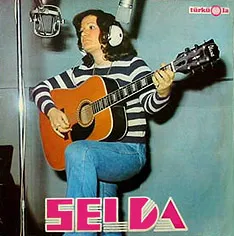

Rapid migration to cities expanded folk’s reach. Radio and LPs popularized regional styles, and urban bağlama orchestras emerged. Folk intersected various currents—protest song, arabesk, and the nascent Anatolian rock—spawning new hybrids while preserving core dance and vocal forms. Master performers like Aşık Veysel and Neşet Ertaş became reference points.

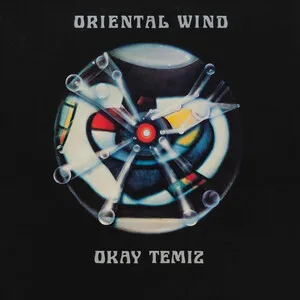

From the 1990s onward, archival revivals, conservatory programs, and world-music circuits broadened the music’s footprint. Artists forged bridges to jazz, rock, and global folk, while local ensembles sustained regional dialects (zeybek, horon, halay, semah). Today, Turkish folk music remains a living tradition—performed at festivals and weddings, taught in institutions, sampled in pop/hip hop, and reimagined by experimentalists—yet still anchored in village poetics and modal-rhythmic nuance.