Maqāmic music is the art-music tradition of the Arabic-speaking world organized around the modal system known as maqām. A maqām defines a scale with characteristic microtonal intervals, a typical melodic pathway (sayr), and a set of melodic building blocks called ajnās (singular: jins). Rather than functional harmony, expression is created through melodic development, ornamentation, and modal modulation.

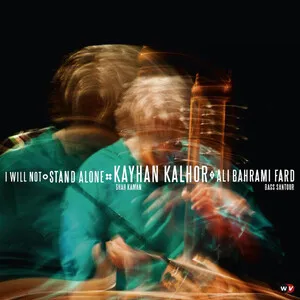

Performances alternate between composed forms and improvisation. Free-rhythm improvisations (taqsīm) explore a maqām’s color and move fluidly between related modes, while metered vocal and instrumental pieces employ cyclical rhythms (iqāʿāt) such as maqsūm, samāʿī thaqīl (10/8), and waḥda. Core timbres include the ʿūd, qānūn, nay, kaman (violin), riqq, and darbuka, with the human voice prized for nuanced intonation of “neutral” intervals (e.g., half-flats). Common forms include muwashshaḥ, qaṣīda, wasla, samāʿī, and taḥmīla.

The maqām concept crystallized during the medieval Islamic Golden Age, drawing on older Near Eastern modal practices. Theoretical foundations appear in works by al-Fārābī (10th c.) and were systematized in 13th‑century Baghdad by Ṣafī al‑Dīn al‑Urmawī, whose intervallic descriptions and tone‑system formulations shaped subsequent practice. Early maqāmic art thrived in courts, urban guilds, and Sufi circles from Iraq and the Levant to Egypt and the Maghreb.

Centuries of cultural exchange under the Ottoman Empire fostered a two‑way dialogue between Arabic maqām and Turkish makam traditions. Shared concepts (ajnas/jins, seyir/sayr, and modal families) expanded modulation practices and repertoire. Parallel developments also interacted with Byzantine chant and Persian art musics, enriching melodic vocabularies and rhythmic cycles.

Urban centers such as Cairo, Aleppo, and Baghdad nurtured professional ensembles and pedagogies. Written collections and early recordings standardized influential repertoires of muwashshaḥāt, wasla suites, and instrumental samāʿī. Ensembles coalesced around the takht (small chamber group) and later the larger firqa, enabling more elaborate orchestration while preserving modal nuance.

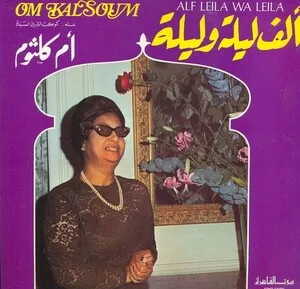

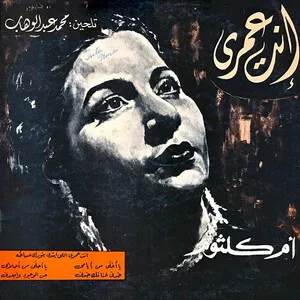

Cairo’s radio era and recording industry amplified maqāmic aesthetics globally. Composers and singer‑composers such as Muḥammad ʿAbd al‑Wahhāb and Riyāḍ al‑Sunbāṭī modernized form, orchestration, and modulation while centering the expressive voice. Iconic vocalists like Umm Kulthum brought maqāmic idioms to mass audiences without abandoning microtonal detail.

Today, maqāmic music thrives in classical, folk‑urban, and popular contexts across the Arab world and diaspora. Conservatories and master‑apprentice lineages teach intonation and sayr orally and through modern notation. Cross‑cultural projects blend maqām with jazz, contemporary classical, and electronic music while maintaining core principles of modal identity, improvisation, and cyclical rhythm.