Your digging level

Description

Ossetian folk music is the traditional music of the Ossetian people of the Central/North Caucasus. It blends heroic epic declamation, stately circle-dance tunes, and intimate lyric songs performed in the Ossetian language (Iron and Digor dialects).

The genre’s signature timbre comes from the fandyr (a three‑string plucked lute), village garmon (diatonic accordion), frame and goblet drums, and unaccompanied or lightly accompanied choral singing with drones and heterophonic textures. Dance pieces often move in measured duple or compound meters suitable for processional circle dances, while epic and ritual songs unfold in flexible, speech‑like rhythms.

Melodically, Ossetian songs favor narrow to moderate ranges, modal inflections akin to Dorian and Mixolydian types, and parallel voice-leading around a sustained tonic drone. Texts cover the Nart epic cycle, toasts and wedding rites, work and seasonal cycles, laments, and lullabies—projecting a palette that ranges from ceremonial and epic to gentle and nostalgic.

Sources: Spotify, Wikipedia, Discogs, Rate Your Music, MusicBrainz, and other online sources

History

Ossetian folk music crystallized over centuries among the Iranic-speaking Ossetian communities of the Central/North Caucasus. While its roots are much older, most systematic documentation dates from the 1800s, when imperial and early ethnographic collectors began notating dances, ritual songs, and epic recitations tied to the Nart saga tradition. The music’s core functions—accompanying dance, anchoring toasts and rites, and narrating heroic lore—shaped its forms, meters, and vocal delivery.

A hallmark instrument is the fandyr, a three‑string long‑neck lute used for solo airs and to accompany singers. By the late 19th century, the garmon (accordion) spread throughout the Caucasus and became central to village dance bands, joined by frame drums and small wind instruments where available. Vocal practices range from solo epic declamation to antiphonal call‑and‑response and small‑choir textures with drone support and heterophony.

Under Soviet cultural policy, Ossetian repertoire was arranged for staged ensembles, state folk choirs, and dance companies. This era produced notated suites for concert halls, standardized stage choreographies (e.g., the stately circle dances), and radio/recordings that preserved many songs. While the staged format favored polished arrangements and broadened audiences, community transmission in villages continued to sustain freer, locally nuanced variants.

Since the 1990s, renewed local and diaspora interest has encouraged archival work, village workshops, and youth ensembles. Contemporary performers mix fandyr and garmon with guitar or small chamber groups, and some projects fuse Ossetian melodies with folk-rock or world‑fusion frameworks while maintaining the dance meters, drones, and modal contours that define the tradition.

How to make a track in this genre

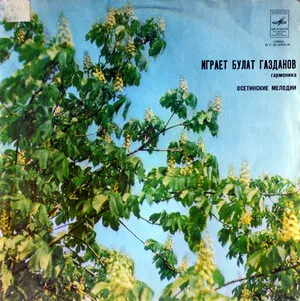

Top albums