Russian folk music is the traditional music of the East Slavic peoples within historic Russia, shaped by pre-Christian ritual song, seasonal and work repertoires, and later by Orthodox-influenced spiritual folk song. It is characterized by open-throated group singing, rich heterophony (multiple voices ornamenting the same melody), drones, and modal melodies that gravitate toward natural minor (Aeolian), Dorian, and Mixolydian flavors.

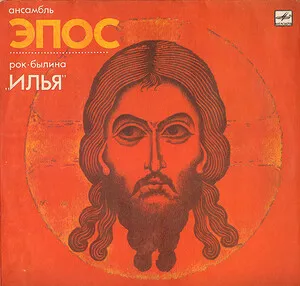

Typical instruments include the balalaika and domra (plucked lutes), gusli (psaltery/zither), garmon and bayan (button accordions), svirel (fipple flute), zhaleika (folk clarinet), and rhythmic idiophones like spoons and treshchotki. Dance and song forms such as khorovod (circle dance), barinya, kazachok, trepak, and the fast, witty chastushka couplet-song are central. The repertoire spans epic byliny (heroic ballads), lyrical laments, wedding songs, harvest and calendar songs, and narrative ballads, often performed in strophic form with call-and-response.

Across centuries, regional and multiethnic interactions in the Volga–Ural and border regions diversified the style’s scales, rhythms, and timbres. In the 20th century, staged folk choirs and orchestras codified a concert style that coexists with village-based traditions and contemporary folk-fusion scenes.

Russian folk music grew from ancient East Slavic ritual and communal practices—calendar songs for spring and harvest, wedding and lament traditions, and epic byliny. These were primarily monophonic but performed heterophonically by groups, often with drones and flexible rhythm suited to outdoor ritual and work contexts. After the Christianization of Rus' (late 900s), Orthodox chant culture and spiritual folk songs (dukhovnyye stikhi) intersected with vernacular practice without replacing it.

From the 18th–19th centuries, scholars, ethnographers, and composers (e.g., the Mighty Handful, Rimsky-Korsakov, Balakirev) collected rural melodies and integrated them into art music, helping codify modes, rhythms, and regional styles. Village ensembles used balalaika, gusli, flutes, and later the garmon/bayan; dance forms like khorovod, trepak, and barinya spread widely. Printed songbooks and phonograph recordings began to preserve and circulate variants.

In the 20th century, state-supported choirs and orchestras (e.g., Pyatnitsky Choir, Osipov Orchestra) standardized a concert style—tight choral blend, staged costumes, expanded orchestration of folk instruments, and arrangements suited to large halls and radio. This coexisted with field-recorded village traditions. The chastushka, work songs, and ritual repertoires remained active, while recording expeditions documented micro-regional styles.

After 1991, a revivalist and experimental wave emerged: ethnographic ensembles preserved micro-regional vocal techniques; singer-songwriters and bands fused folk with rock, pop, and electronics; and global scenes (world-fusion, folk metal, neofolk) adopted Russian modalities and timbres. Today, archival work, community festivals, and academic programs sustain both the living village traditions and the concert/urban folk scenes.

Russian folk music shaped national identity and influenced art music, Russian romance, urban song, and contemporary fusion genres. Its hallmarks—heterophony, modal color, drones, and communal performance—remain instantly recognizable.