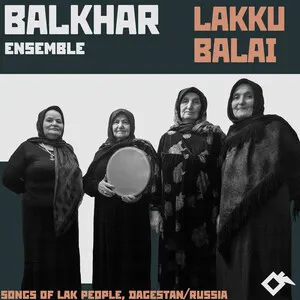

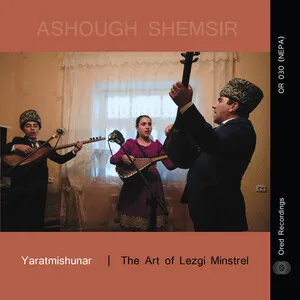

Dagestani folk music encompasses the traditional musics of the Republic of Dagestan in the North Caucasus, where dozens of ethnic groups (Avar, Dargin, Lezgi, Kumyk, Lak, Tabasaran, Rutul, Tsakhur, Nogai, and others) have distinct yet interrelated styles.

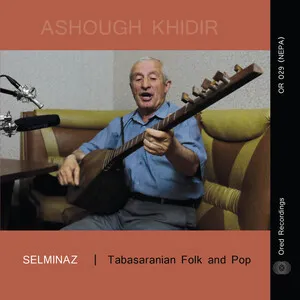

Its core sound blends high‑energy dance rhythms (especially for the pan‑Caucasian lezginka) with ornamented, modal singing. Lead instruments often include the zurna/surnai and balaban double reeds, the kamancha bowed lute, and the garmon (Caucasian button accordion), supported by drums such as the naghara/dhol and frame drums (dap/ghaval). Saz‑type long‑neck lutes and shepherd flutes (tutek/kaval) are also heard. Textures are typically heterophonic, with drones and tight unison lines embellished individually.

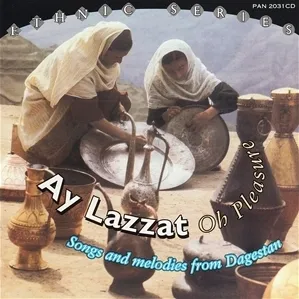

The music is deeply functional—performed at weddings, communal celebrations, warrior/epic recitations, and seasonal or religious occasions—while retaining strong Islamic and maqam/mugham inflections in vocal style and melody.

Dagestani folk music emerged from the musical lives of multiethnic mountain and lowland communities in the North Caucasus. Shepherding, agricultural cycles, and clan ceremonies shaped epic song, dance music, and work songs. With the spread of Islam (from the Middle Ages onward) came devotional genres and an increased emphasis on ornamented, modal vocalism akin to maqam/mugham practice—especially in the Caspian lowlands around Derbent where cultural exchange with Azerbaijan and Persia was intense.

During the 1800s, travelers and imperial ethnographers began notating and describing regional repertoires and instruments. Public salons and urban festivities helped standardize popular dance types such as the lezginka, which became emblematic of the Caucasus and a vehicle for interethnic musical exchange across Dagestan’s peoples.

In the Soviet period, republic‑level song‑and‑dance ensembles and folk orchestras were established. Local styles were arranged for stage, mixing traditional reeds, lutes, and percussion with concert garmon parts and choral writing. Radio and recording archives in Makhachkala and Moscow preserved field recordings, while conservatories fostered composers who integrated Dagestani themes into concert works.

After 1991, wedding circuits, festivals, and diaspora communities sustained demand for traditional performance. Cross‑border collaboration with neighboring Caucasian and Caspian regions intensified, and younger artists fused lezginka rhythms and modal turns with pop, hip‑hop, and electronic production. Contemporary projects often restore village repertoires while digitizing archives for broader access.

Dagestani folk music remains socially central—especially in rites of passage—while thriving on stages via professional ensembles. Its distinctive meters, heterophony, and reed‑drum energy continue to influence Caucasian popular culture and world/roots projects beyond the region.