Islamic religious music and recitation encompasses the sacred vocal arts of Islam, centered on Qur'an recitation (tilāwah/tajwīd), the call to prayer (adhān), devotional chant (dhikr), praise poetry (madīh, na‘t), and paraliturgical song traditions such as nasheed, qasidah, and Sufi samā‘.

While many Muslims distinguish Qur'anic recitation from "music" and regard it as a unique sacred art bound by rules of tajwīd and pious intent, its sound-world overlaps with regional musical systems (especially the Arabic maqām tradition) through modal nuance, melisma, and ornamentation.

Across regions, the genre ranges from unaccompanied, metrically free recitation and adhān, to percussion-accompanied nasheed, and to more elaborate Sufi traditions (e.g., qawwali) with call-and-response, rhythmic cycles, and ecstatic crescendos—all unified by devotional texts, ethical themes, and reverence for the divine.

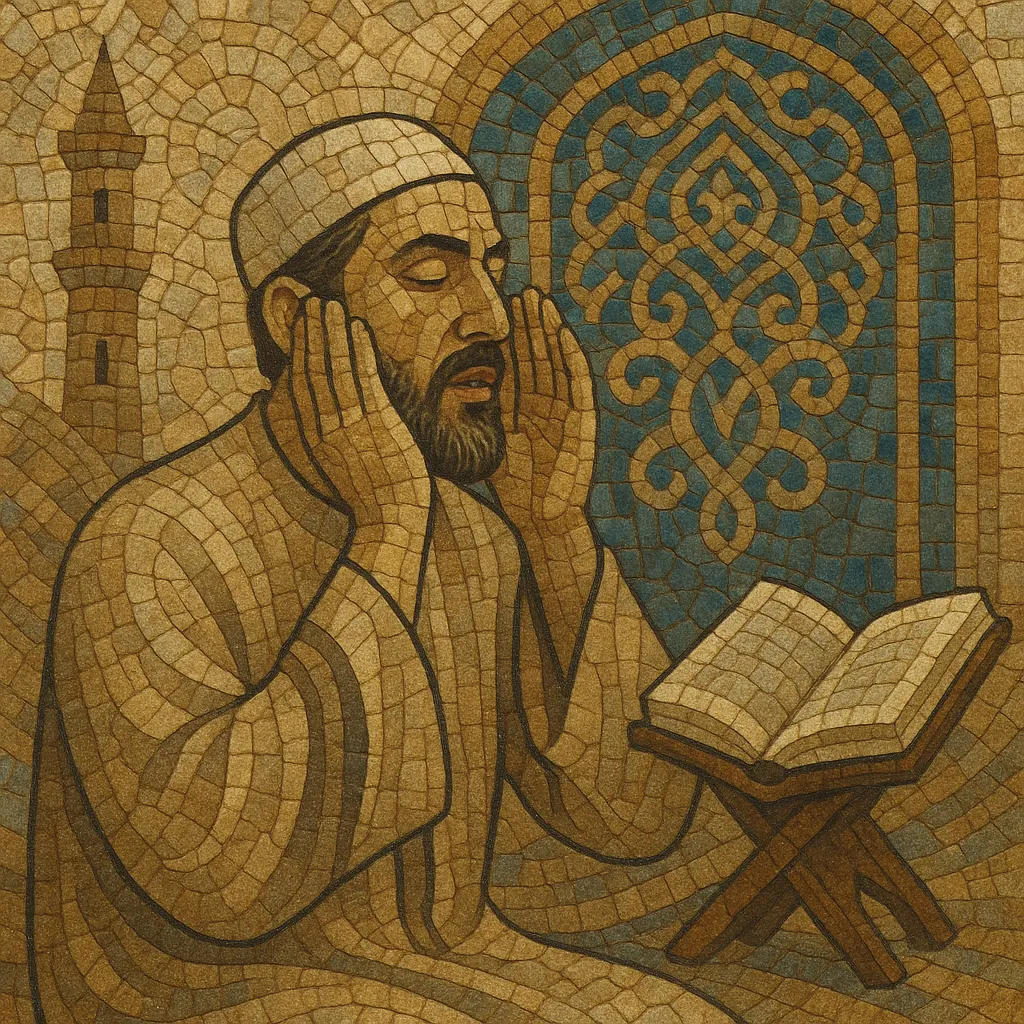

Islamic sacred vocal practice originates with the revelation of the Qur'an in the early 600s in the Hijaz (present-day Saudi Arabia). The Prophet Muhammad encouraged the beautification of the voice in recitation, and the adhān (call to prayer) emerged to mark prayer times. Early recitation emphasized precise pronunciation (tajwīd), clarity (tafkhīm/tarqīq), and a reverent delivery rather than entertainment.

As Islam spread, recitation styles interacted with local aesthetics and modal conceptions—especially the Arabic maqām system. Parallel devotional forms grew: dhikr (remembrance of God), madīh (praise of the Prophet), and qasidah (ode). Sufi orders developed samā‘ (spiritual audition) practices, creating regionally distinct devotional musics: the Mevlevi in Anatolia, inshād in the Arab world, and qawwali in South Asia.

Ottoman, Persian, Maghrebi, and South Asian courts and khānqāhs (Sufi lodges) cultivated refined ceremonial musics that, while often para-liturgical, drew on sacred texts and ethics. Mosque-based arts (recitation and adhān) remained largely unaccompanied and non-metric. In Indonesia and the Malay world, Arabic-influenced devotional singing blended with local languages and meters, leading to forms like sholawat and qasidah.

Radio, cassettes, satellite TV, and streaming popularized legendary reciters (e.g., Al-Hussary, Abdul Basit) and spread adhān styles internationally. Nasheed expanded from a cappella to polished studio productions (often with frame drums or minimal percussion), and Sufi genres like qawwali reached global audiences. Contemporary debates continue about instruments and performance contexts, but the core ideals—accurate articulation, piety, modesty, and spiritual uplift—endure.

Across all strands, the voice is primary, text is paramount, and delivery balances modal beauty with spiritual intentionality. Even when musical accompaniment is used (in nasheed or Sufi traditions), texts avoid profane themes, and performance etiquette emphasizes humility and devotion.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)