Kurdish music is the traditional and contemporary music of the Kurdish people, spanning the mountainous regions of present‑day Iraq, Turkey, Iran, and Syria. It centers on modal melodies, rich vocal ornamentation, and poetic storytelling, and it ranges from unaccompanied epic singing (dengbêj) to driving dance music for circle dances (govend/halay).

Its melodic language is closely tied to Near Eastern modal systems (maqam/dastgāh), with characteristic use of the Kurd/Bayât‑e Kurd mode (akin to a minor scale with a lowered second) and related hijaz/bayat families. Common meters include 2/4 and 6/8 for dances, alongside asymmetrical meters such as 7/8 and 9/8. Typical instruments include the tembûr/tanbur and saz (bağlama), frame drums (daf) and double-headed drums (dohol), reed and double‑reed winds (ney, zurna, balaban/duduk), as well as kamancheh and violin; modern ensembles may add keyboards and electric bağlama.

Lyrically, Kurdish songs are often performed in Kurmanji, Sorani, and Zazakî, exploring themes of love, nature, heroism, exile, and resistance. The sound can be at once melancholic and epic, yet also celebratory and communal in its dance repertoires.

Kurdish music has deep oral roots that predate recording, with itinerant singer‑poets (dengbêj) preserving history and collective memory through narrative song. Its melodic vocabulary aligns with West Asian modal systems—maqam in the Arab world and dastgāh/âvâz in Iran—while Kurdish regional practices developed distinct modal flavors (e.g., Bayât‑e Kurd) and dance repertoires.

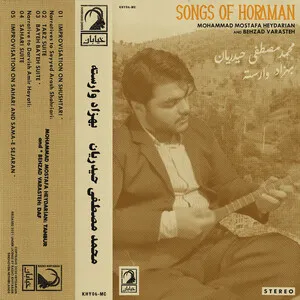

The modern codification of “Kurdish music” as a recorded genre dates to the early 1900s, with gramophone discs and later radio broadcasts (notably in Baghdad and other urban centers) disseminating Kurdish songs beyond local communities. Pioneering singers such as Meryem Xan and Ali Merdan helped define a recorded style that balanced traditional modal phrasing with emerging studio aesthetics.

From the 1950s to the 1980s, celebrated voices like Hesen Zîrek, Eyşe Şan, and Şivan Perwer broadened the canon, despite political constraints and periodic suppression of Kurdish language and culture—especially in Turkey and parts of Syria and Iraq. Exile networks and diaspora venues kept the music alive, circulating cassette culture and live recordings that nurtured a pan‑Kurdish sound.

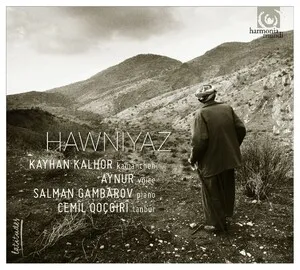

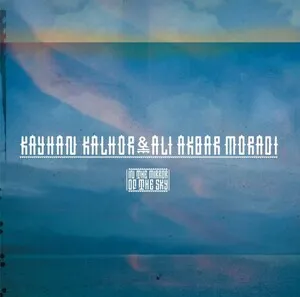

Since the late 20th century, Kurdish music has flourished in both homeland and diaspora, integrating elements of Turkish/Arab/Iranian pop, rock, and global fusion while maintaining core modal and poetic characteristics. Artists such as Ciwan Haco, Nizamettin Arıç, Mazhar Khaleghi, and Aynur Doğan have bridged traditional and modern sensibilities, bringing Kurdish music to international stages and film soundtracks.

Contemporary Kurdish music spans intimate dengbêj recitals, festival‑scale dance bands, and cross‑genre collaborations. Digital platforms have amplified regional styles (Kurmanji, Sorani, Zazakî), ensuring both preservation of heritage and ongoing stylistic innovation.