Your digging level

Description

Shidaiqu ("songs of the era") is a cosmopolitan style of Chinese popular music that flourished in Republican‑era Shanghai.

It blends Western dance‑band jazz, swing, tango and rumba rhythms with Chinese melodic sensibilities, especially pentatonic tunes and ornamented, lyrical vocal lines.

Songs were typically performed in Mandarin (and sometimes Shanghainese) by film and radio stars, arranged for dance bands or light orchestras, and associated with nightclubs and cinema.

The style’s suave melodies and urbane lyrics captured the modern, international spirit of 1930s Shanghai while remaining recognizably Chinese in phrasing and vocal delivery.

History

Shidaiqu emerged in treaty‑port Shanghai, where gramophone labels, dance halls, and cinemas fostered a new urban entertainment industry. Composer–bandleader Li Jinhui is widely credited as the style’s architect, promoting Mandarin popular songs that married Chinese pentatonic melodies to Western dance rhythms and jazz harmonies. Early recordings and film musicals helped standardize the sound and spread it across Chinese‑speaking markets.

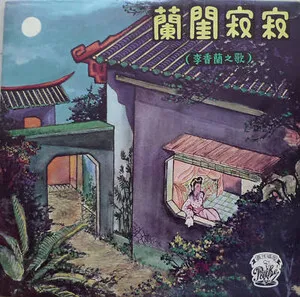

During Shanghai’s “golden age,” shidaiqu flourished in nightclubs, radio, and cinema. Swing‑era instrumentation (saxes, trumpets, piano, guitar, bass, drums) supported graceful, ornamented vocals delivered by glamorous stars. The “Seven Great Singing Stars”—including Zhou Xuan, Yao Li (Yao Lee), Bai Guang, Bai Hong, Gong Qiuxia, Li Xianglan (Yoshiko Yamaguchi), and Wu Yingyin—popularized the repertoire with romantic, urbane songs that balanced Western dance feels with Chinese phrasing.

The Sino‑Japanese War and occupation disrupted the industry, but recording and film production continued under difficult conditions, and the style’s cross‑regional popularity grew. After 1945, shidaiqu’s dance‑band elegance remained emblematic of prewar modernity even as tastes diversified.

Following 1949, shidaiqu was condemned as “yellow music” on the mainland, prompting artists, composers, and producers to move to Hong Kong and, to a lesser extent, Taiwan. There, the idiom evolved into early Mandarin pop and helped seed the infrastructures and aesthetics that later blossomed into Mandopop and Cantopop. Grace Chang (Ge Lan), Chang Loo, and others carried the repertoire into postwar film musicals and nightclubs, updating arrangements with contemporary Latin and light‑jazz colors.

Shidaiqu is now regarded as the foundational form of modern Chinese pop. Its sophisticated marriage of Western harmony/rhythm with Chinese melodic style set a durable template for later C‑pop, influencing vocal delivery, songwriting forms (AABA/verse‑chorus), and the central role of cinema and recording in star‑making.

How to make a track in this genre

Use a small dance band or light orchestra: vocals, piano, acoustic/electric guitar, double bass, drum set with brushes, and a horn section (clarinet/saxophone, trumpet). Strings or accordion can add period sweetness. Optional Chinese timbres (erhu, dizi) can be used sparingly for color.

Base songs on elegant social‑dance feels: foxtrot and slow swing in 4/4; rumba (with a gentle clave feel) or tango/habanera patterns for Latin inflection; occasional waltz in 3/4. Keep tempos moderate and danceable, prioritizing lilt and grace over drive.

Write with Western functional harmony (I–vi–ii–V, secondary dominants, diminished passing chords) and lush extensions (6ths, 7ths, 9ths). Common forms are 32‑bar AABA and verse–chorus. Modulations up a half‑step or whole‑step can heighten finales.

Craft singable, pentatonic‑leaning melodies with stepwise motion and tasteful ornaments (slides/portamento, light vibrato). The vocal tone should be poised, intimate, and slightly breathy, with clear Mandarin diction (or period Shanghainese) and elegant phrasing that floats over the beat.

Focus on urban romance, nights on the Bund, longing, modern fashion, and cosmopolitan life. Use refined, slightly poetic imagery; avoid slangy directness. Refrains should be memorable and emotionally resonant.

Balance horns and reeds with soft rhythm‑section brushwork; double melodies with violin/clarinet for warmth. Employ call‑and‑response fills between voice and sax/clarinet. In production, keep mixes natural and intimate, with subtle plate‑style reverb to evoke vintage rooms. Endings often use a ritard and a gentle final tag.

%20%2F%20%E5%A4%A9%E6%B6%AF%E6%AD%8C%E5%A5%B3%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)