Your digging level

Description

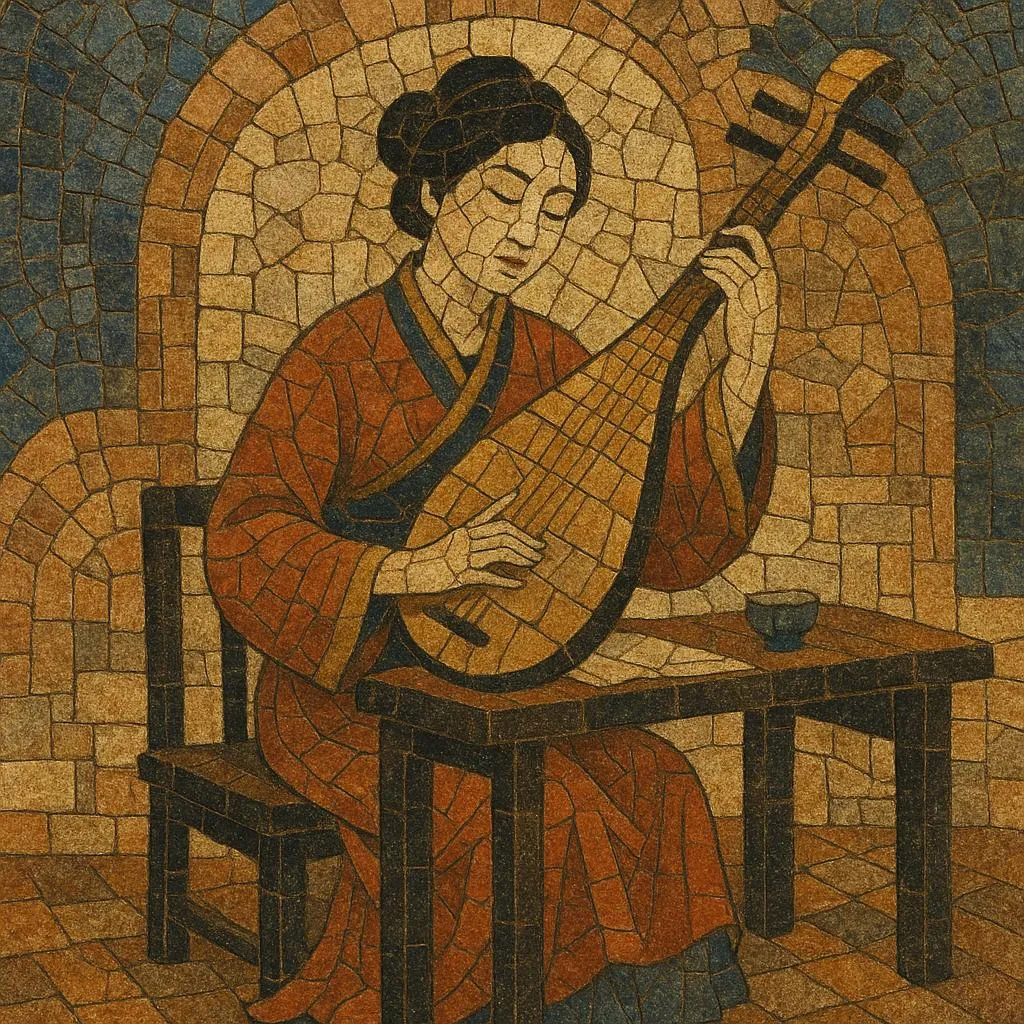

Tanci (literally “plucking rhymes,” 弹词) is a southern Chinese narrative song form that alternates between sung verse and spoken prose.

The verse portions are commonly written in seven-character lines (with occasional ten-character lines) and are performed to the accompaniment of a plucked lute—traditionally the pipa—often joined by sanxian or other soft Jiangnan instruments.

As a storytelling art, tanci blends literary diction with regional speech, and it is typically delivered in Wu-Mandarin timbres in the Jiangnan area. Its local traditions include Suzhou Tanci, Yangzhou Tanci, Siming Nanci (Ningbo area), and Shaoxing Pinghudiao. Audiences historically encountered tanci in teahouses and salons, where performers sat at a small table, interweaving lyrical singing with spoken narration to sustain long-form plots drawn from romance, history, and morality tales.

History

Tanci took shape in the Jiangnan region during the Qing dynasty, reaching mature form by the 18th century. The alternation of sung verse and spoken prose allowed storytellers to pace long narratives while maintaining audience engagement. The core instrumental color came from the pipa (and sometimes sanxian), aligning the genre with the refined, chamber-like aesthetics of Jiangnan music.

From the late 18th to 19th centuries, educated women wrote influential tanci cycles, adapting popular romance and historical materials into elegant heptasyllabic verse. These works circulated in manuscript and print among literati circles, and some made their way into performance repertoires. The best-known cycles demonstrated how tanci could serve both as an art of public storytelling and a literary vehicle for private reading and salon performance.

By the 19th and early 20th centuries, distinct local styles crystallized: Suzhou Tanci (the best-known), Yangzhou Tanci, Siming Nanci (Ningbo), and Shaoxing Pinghudiao. Performers standardized sitting-stage conventions (a small table, clappers, and teahouse staging) and cultivated signature singing styles and stock narrative routines. The broader umbrella of “pingtan” in Suzhou (combining narrative speaking and narrative singing) helped institutionalize training and repertoire.

In Republican-era Shanghai, tanci benefited from urban teahouse culture, printed libretto circulation, and early recording and broadcast media. After 1949, troupes (e.g., Suzhou/Shanghai Pingtan companies) systematized pedagogy and repertory, while researchers documented local variants. In recent decades, festivals, conservatory projects, and digitization have supported revival, and tanci aesthetics and narrative techniques continue to inform new stage productions and stylistic fusions.