Your digging level

Description

Polyphonic chant is a sacred vocal tradition in which two or more independent voices sing liturgical material at the same time, creating vertical harmony from originally monophonic chant.

Emerging from the practice of adding a second voice to chant (organum), it favors perfect consonances (fourths, fifths, and octaves) and often places a sustained chant line (tenor) beneath more florid upper parts. In its classic medieval Western form, it is unaccompanied (a cappella), modal rather than tonal, and frequently governed by rhythmic modes. While the Notre Dame school in Paris codified much of its technique, related polyphonic chant practices also exist in other liturgical cultures (e.g., Georgian and Corsican traditions), each with distinctive sonorities and voice-leading norms.

History

The earliest documented polyphony in Western Europe appears in Carolingian-era treatises such as the Musica enchiriadis (late 9th century), which describes parallel and oblique organum—adding a second voice to a chant at the interval of a fourth or fifth. By the 11th century, more flexible note-against-note (free organum) emerged in centers like St. Martial of Limoges and in sources such as the Winchester Troper.

The Notre Dame school in Paris—associated with Léonin and Pérotin—transformed polyphonic chant into sophisticated multi-voice textures. They introduced rhythmic modes (patterns of long–short durations) and developed sustained-note (tenor) organum, discant sections, and early clausulae that paved the way for the motet. This period (often termed Ars antiqua) established techniques of voice-leading, cadence formulas on perfect consonances, and large-scale liturgical polyphony for the Mass and Office.

Following Notre Dame, polyphonic chant practices spread across Europe, influencing conductus and, crucially, the motet. By the 14th century, polyphony diversified further in Ars nova, but chant-based tenor techniques and modal thinking continued to inform sacred composition. In parallel, other liturgical cultures—especially Georgian and Corsican traditions—nurtured distinctive polyphonic chant lineages with their own tuning preferences and texture types (e.g., drones, parallel seconds, or open fifths).

Polyphonic chant underpins the evolution of Western choral music: it leads directly to the Renaissance motet and Mass cycles, shapes contrapuntal pedagogy (species counterpoint’s preference for perfect consonances and controlled dissonance), and ultimately informs Baroque and later choral idioms. Modern early-music ensembles have revived medieval repertories, while living polyphonic chant traditions (e.g., Corsican paghjella, Georgian liturgical polyphony) keep the aesthetic vibrant in contemporary performance.

How to make a track in this genre

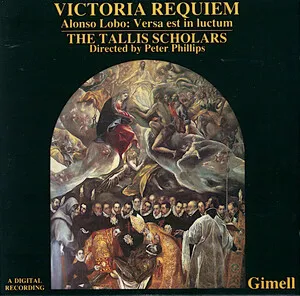

Top albums