Medieval classical music refers to the notated art music of Europe during the Middle Ages (roughly the 6th to the late 14th century). It encompasses sacred and secular traditions, moving from largely monophonic chant to the first structured polyphony, and establishing many of the foundations of the Western classical tradition.

At its core are liturgical repertoires (especially Latin chant) and the emergence of measured rhythm, modal theory, and contrapuntal procedures. Later medieval innovations—such as organum, motet, isorhythm, and the formes fixes—shaped the musical language that would lead into the Renaissance.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Christian liturgy became the central context for cultivated music. Plainchant (especially the Frankish-Roman synthesis later called Gregorian chant) was codified and disseminated through Carolingian reforms. Early neumatic notation emerged to aid memory, establishing the first stable system for preserving melodies.

The 12th century saw the systematic development of polyphony—especially at the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris. Composers such as Léonin and Pérotin expanded chant into organum with independent upper voices and introduced rhythmic modes, giving measured organization to music. This period also witnessed the rise of the motet, created by adding new texts to clausulae, sometimes layering different texts simultaneously.

Alongside sacred repertories, vernacular song flourished. In southern France, troubadours (e.g., Bernart de Ventadorn) cultivated refined lyric poetry in Occitan; their northern counterparts, the trouvères (including Adam de la Halle), set courtly themes in Old French. In the German lands, Minnesänger like Walther von der Vogelweide developed analogous traditions. These repertoires favored strophic forms and modal melodies, often accompanied by instruments.

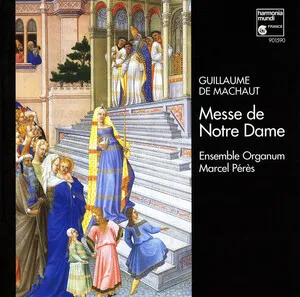

In the 14th century, the Ars Nova (Philippe de Vitry, Guillaume de Machaut) introduced innovations in mensural notation, allowing complex rhythmic divisions (duple and triple) and isorhythmic techniques in motets. The formes fixes (ballade, rondeau, virelai) became key poetic-musical structures. The late century’s Ars Subtilior pushed rhythmic and notational complexity to extremes, anticipating later explorations of metric play.

By the late 14th century, modal counterpoint, written notation, and formal design were firmly established. These foundations led directly into the Renaissance—shaping polyphonic texture, vocal ensemble writing, and the choral tradition that underpins Western classical music.