Your digging level

Description

Indigenous American music is the collective term for the ceremonial, social, and everyday musical practices of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, spanning the Arctic to Tierra del Fuego. It encompasses thousands of community-specific traditions with distinct languages, scales, timbres, instruments, and functions.

While its roots predate written history, common traits include the central role of voice and percussion (large powwow drums, water drums, frame drums, rattles), extensive use of vocables, call-and-response or responsorial forms, cyclical rhythms tied to dance, and melodic shapes that may emphasize pentatonic or anhemitonic scales. In the Andes, aerophones like panpipes (siku/antara) and quena flutes are foundational, often played in interlocking hocket textures; in the Arctic, throat singing traditions (katajjaq) feature timbral games and rhythmic breath exchanges.

Music functions as living knowledge—binding cosmology, history, territory, and community—appearing in healing, agriculture, hunting, diplomacy, resistance, and celebration. Modern Indigenous artists continue these lineages while innovating across folk, rock, electronic, hip-hop, and experimental forms.

Sources: Spotify, Wikipedia, Discogs, Rate Your Music, MusicBrainz, and other online sources

History

Indigenous American music long predates written records, emerging with the earliest communities of the Americas. Songs, rhythms, and instruments were embedded in ceremonial life, subsistence cycles, and oral histories. Because music was inseparable from language, land, and spirituality, each nation developed highly specific repertoires—powwow songs on the Plains, sikuri panpipe ensembles in the Andes, Iroquoian social dances, and Arctic throat singing among Inuit and related peoples.

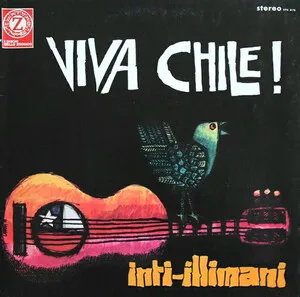

European invasion and colonialism disrupted lifeways, yet Indigenous musical practices persisted, adapted, and often syncretized. Mission settings introduced new instruments (violins, guitars), hymnody, and notational practices, which some communities indigenized. Across Latin America, many mestizo and criollo forms—such as huayno and, later, cumbia—carry strong Indigenous rhythmic, melodic, and instrumental DNA alongside Iberian and African elements.

Early ethnographers and Indigenous knowledge-keepers documented songs on cylinder and tape, while powwow culture expanded as a pan–Indigenous social space. The folk revival and civil rights era lifted voices like Buffy Sainte-Marie and community drum groups, reframing Indigenous music as contemporary and political as well as traditional. Community-controlled labels and radio helped return stewardship to Indigenous artists.

Today, Indigenous American music thrives across ceremonies and global stages alike. Artists fuse traditional song forms and languages with rock, hip-hop, electronic, and experimental production. Powwow drums, Native flutes, Andean panpipes, and throat singing sit alongside samplers and synths. The result is resilient continuity: music as living heritage, sovereignty, and innovation.