Amazigh music (also called Berber music) encompasses the diverse musical traditions of the Indigenous Amazigh peoples across the Maghreb and Sahara, especially in Morocco and Algeria, with extensions into Tunisia, Libya, Mali, and Niger.

It is characterized by cyclical, trance-inducing rhythms, antiphonal (call-and-response) vocals, poetic text forms (such as izlan and tamawayt), and a strong communal dimension expressed through participatory dances like ahidus (Middle/High Atlas) and ahouach (Souss/Anti-Atlas). Core timbres come from frame drums (bendir, tbel), handclaps, and plucked or bowed lutes—lotar and ribab in southern Morocco, imzad among Saharan Amazigh, and later the acoustic/electric guitar. Modal melodies often hover around narrow ambitus lines, with ornamented, melismatic singing; in Saharan (Tuareg/Tamasheq) areas, pentatonic figures and droning guitar ostinati are common.

While fundamentally an ancient folk tradition transmitted orally in Tamazight languages (Tachelhit, Tarifit, Central Atlas Tamazight, Kabyle, Tamasheq), modern Amazigh music spans acoustic poetry, electrified folk-pop, and desert blues, engaging urban idioms and studio production while maintaining its poetic, communal, and rhythmic core.

Amazigh music predates Islam in North Africa and was maintained through oral transmission in village, oasis, and nomadic settings. Poet-musicians (rways/rwayes in the Souss, imdyazen in the Atlas) preserved love poetry, satire, moral tales, and communal history in Tamazight dialects, accompanying themselves on lotar or ribab with bendir and handclaps. Circle dances like ahidus and ahouach fostered collective participation and call-and-response singing.

From the medieval period onward, Amazigh communities interacted with urban Andalusi/Arab traditions. Andalusian classical (nūba) aesthetics and Moorish court culture diffused modal and poetic sensibilities into the region, while Amazigh rhythms and performance formats influenced local urban musics. Instruments and craft techniques circulated between rural, courtly, and Sufi contexts.

Shellac and radio in colonial Casablanca, Algiers, and Rabat captured early Amazigh performers, but representation was uneven. After independence (1950s–60s), cultural assertion fueled a folk revival. In Morocco, rways modernized stage formats; groups like Izenzaren and Oudaden electrified Amazigh songs in the 1970s. In Algeria, Kabyle artists like Idir and Lounis Aït Menguellet brought Amazigh poetry and melody to national and international audiences.

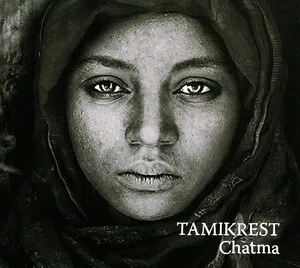

The 1980 “Berber Spring” highlighted linguistic and cultural rights in Algeria, and iconic figures such as Matoub Lounès amplified resistance, identity, and memory through song. In the Sahara, Tuareg/Tamasheq musicians—many displaced by conflict—developed guitar-driven desert blues (tishoumaren), later popularized globally by Tinariwen and peers.

Amazigh music thrives across festival circuits (e.g., Timitar in Agadir), broadcast media (Tamazight TV in Morocco), and global stages. Artists blend traditional poetry and rhythms with pop-rock, chaabi, reggae, and electronic production while maintaining Amazigh linguistic and poetic identity. Archival projects and community initiatives document rural repertoires, and younger generations revive dance-chorus traditions alongside studio-crafted folk-pop.