Vietnamese music is an umbrella term for the traditional, court, folk, and popular musics created and performed by the peoples of Vietnam.

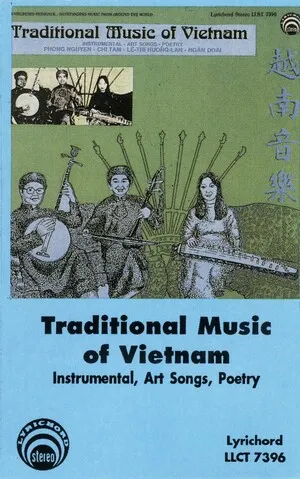

At its core are pentatonic melodic systems, flexible rhythms, and heterophonic textures shared among regional folk styles (such as quan họ, ca trù, chèo, tuồng, and cải lương) and the imperial court repertory (nhã nhạc). Indigenous instruments like đàn bầu (monochord), đàn tranh (zither), đàn nguyệt (moon lute), đàn nhị (fiddle), sáo trúc (bamboo flute), and a family of drums and clappers shape its timbre.

From the 19th–20th centuries onward, Vietnamese music absorbed outside influences—Sinitic court and opera traditions, Khmer and Cham regional elements, French chanson and salon music, Latin bolero, Soviet mass song aesthetics, and later American jazz, rock, and pop—leading to modern forms ranging from nhạc đỏ and nhạc vàng to contemporary V-pop and hip hop. Lyrically, themes often revolve around love, nature, memory, homeland, and moral reflection, expressed through ornate vocal ornamentation or sleek, modern pop production.

Vietnamese musical practices trace back many centuries, with formal court repertories maturing under the Lý (11th–12th c.) and later dynasties. Imperial "nhã nhạc" (elegant music) codified ceremonial ensembles, dances, and vocal pieces, using pentatonic modal frameworks, heterophonic textures, and refined ornamentation. Parallel to court practice, regional folk traditions (northern quan họ antiphonal duets, northern ceremonial poetry-song ca trù, northern stage genres chèo and tuồng, and southern cải lương) formed rich local ecosystems tied to festivals, craft guilds, and communal houses.

Centuries of cultural exchange with China shaped court music and opera forms, while Khmer and Cham communities influenced southern repertories and instrumental practice. Under French colonial rule, salon music, chanson, and urban dance repertoires entered Vietnamese cities, leading to new hybrid song forms and the modernization of instruments and notation.

After 1954, musical life diverged. In the North, state-sponsored "nhạc đỏ" (revolutionary songs) drew on Soviet/Eastern Bloc mass song aesthetics, choral writing, and patriotic themes. In the South, "nhạc vàng" (prewar/postwar sentimental pop) and Latin-derived bolero flourished alongside electric bands influenced by jazz, rock and roll, and later surf and soul. The wartime period also produced prolific songwriting (e.g., Trịnh Công Sơn), balancing poetic introspection with contemporary harmonies.

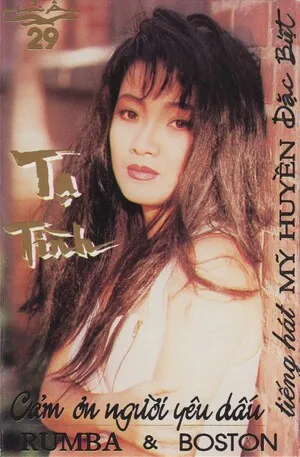

Following reunification, public music initially prioritized revolutionary themes, while overseas Vietnamese communities (especially in the U.S. and France) preserved and developed pre‑1975 popular styles through variety programs and recording industries. Economic reforms (Đổi Mới, from 1986) loosened cultural policy, reinvigorating traditional arts and allowing broader pop imports. Conservatories and troupes continued to document and revive court and folk genres, culminating in UNESCO recognitions for several traditions.

Digital platforms catalyzed V‑Pop’s idol system, EDM‑inflected production, and slick visuals, while indie scenes and hip hop (rap in Vietnamese and regional dialects) gained mainstream presence. Contemporary artists increasingly fuse pentatonic motifs, folk timbres, and historical imagery with modern pop, R&B, and trap, projecting Vietnamese music globally while maintaining deep ties to poetic language and traditional aesthetics.