Buddhist music is the broad family of liturgical chant and ritual sound practices associated with Buddhist traditions across Asia. It centers on the vocal recitation of sutras, mantras, and dhāraṇīs, often performed a cappella by monastics or lay chanters, and is designed to aid concentration, devotion, and the transmission of teachings.

While primarily vocal and modal, instrumentation appears in many regional practices: Tibetan rituals feature low multiphonic chant with drums, large cymbals, horns, and shawms; Chinese fanbai and Korean beompae retain courtly timbres; Japanese shōmyō emphasizes refined, unison vocal lines; and Theravāda communities in Southeast Asia maintain austere Pāli chant with minimal or no accompaniment. Common traits include restricted melodic ambitus, formulaic melodic contours, free or flexible rhythm, and text-forward delivery in sacred languages such as Pāli, Sanskrit, Tibetan, Chinese, Korean, and Japanese.

Buddhist musical practice grows out of early monastic recitation in the Indian subcontinent, where orally transmitted chant supported the memorization and performance of sutras, mantras, and doctrinal lists. Its earliest forms were primarily unison, syllabic or lightly melismatic, and closely tied to the prosody of Pāli and Sanskrit. While precedents exist earlier, Buddhist chant crystallized as a recognizable liturgical practice by the 4th–5th centuries CE as Buddhism institutionalized across monasteries.

As Buddhism spread along the Silk Road, its chant traditions localized. In China, Buddhist chant (fanbai) interacted with court ritual (yayue) and temple music, shaping distinctive tonal contours and ceremonial formats. Korea developed beompae, a learned monastic chant tradition with stylized delivery and ceremonial roles. Japan established shōmyō in the Nara–Heian periods, emphasizing refined ensemble unison, breath discipline, and codified melodic formulas.

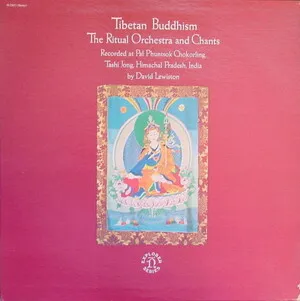

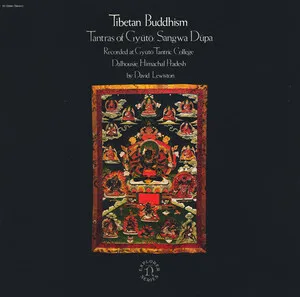

In the Himalayan sphere, Tibetan Buddhist liturgy developed low-pitched overtone (miphonic) chant and richly orchestrated ritual ensembles (drums, gongs, cymbals, long horns, double-reed gyaling), aligned with Vajrayāna ritual cycles. Theravāda communities across Sri Lanka, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Myanmar preserved Pāli paritta chanting with austere textures and free rhythm.

From the 20th century onward, recordings by Tibetan monastic choirs and Japanese shōmyō ensembles brought Buddhist music to global audiences. Contemporary composers and new age artists adapted mantras and chant textures for concert and meditative contexts, while diaspora communities maintained liturgical practice. Today, Buddhist music encompasses both conservative liturgy and new contemplative fusions, remaining a living devotional practice and an influential template for meditative and ambient soundscapes.