Your digging level

Description

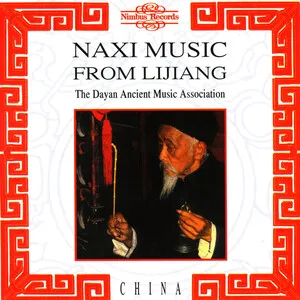

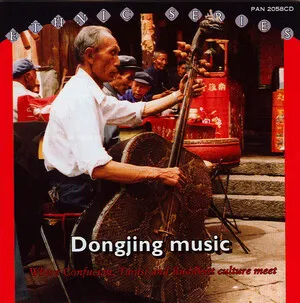

Naxi music refers to the musical traditions of the Naxi people of southwest China, especially around Lijiang in Yunnan.

It blends broader Chinese musical systems (pentatonic melodic thinking, court/ritual repertories, and ensemble practices) with distinctly local Naxi aesthetics, language, and ceremonial life.

A widely recognized core within “Naxi music” is Naxi ancient music (Naxi gu yue), an ensemble tradition that preserves older repertories and performance practices associated with classical Chinese instrumental music as maintained in Naxi communities.

Typical sound features include heterophonic ensemble texture (multiple instruments ornamenting the same melody), flexible phrasing shaped by breath and bowing, and timbres from plucked lutes, bowed strings, and bamboo winds.

History

Naxi musical life formed within the cultural networks of southwest China, where local ritual practices interacted with Chinese court and literati traditions carried through trade, administration, and migration.

Over centuries, Naxi communities preserved and adapted older instrumental pieces and ceremonial music, transmitting them through local lineages and community ensembles. The repertory remained closely tied to ritual occasions, social gatherings, and local cultural identity.

In the 20th century, especially after the mid-century, concert presentation and cultural documentation increased. Ensembles in and around Lijiang became known for presenting “Naxi ancient music,” framing parts of the tradition as a living archive of older Chinese instrumental styles maintained by Naxi performers.

Today, Naxi music continues both as community practice and as staged performance for cultural preservation and tourism. Modern documentation has also encouraged educational projects, instrument standardization, and repertoire archiving, while some musicians experiment with cross-genre collaborations.

How to make a track in this genre

Build a small to medium ensemble with a mix of plucked strings, bowed strings, and bamboo winds. Typical choices include:

• Plucked: pipa, sanxian, ruan, or local lutes • Bowed: erhu (or related bowed fiddles) • Winds: dizi/xiao-like flutes or local bamboo winds • Support: small percussion for marking entrances or ceremonial emphasis (often restrained)Write singable, pentatonic-centered melodies, then allow ornamental variants.

• Start with a clear melodic skeleton. • Add grace notes, turns, slides, and subtle rhythmic stretching. • Keep phrases balanced, often shaped by breath (for winds) or bow direction (for strings).Aim for heterophony rather than strict harmony:

• Give all melodic instruments the same tune. • Ask each instrument to decorate it differently (timbral color and ornament density). • Stagger ornament placement so the line stays intelligible while sounding richly layered.Use flexible, speech-like timing rather than heavy backbeat:

• Employ moderate or slow tempos for ceremonial and reflective pieces. • Organize music in short sections with repeated strains, allowing variation on each repeat. • Use percussion sparingly, mainly to punctuate transitions or formal cadences.Avoid Western chord progressions as the primary driver.

• Let drones, open fifths, and occasional parallel motion appear naturally from the instruments. • If you add harmony, keep it minimal and supportive (sustained tones, lightly implied cadences).Prioritize expressive nuance:

• Intonation should be carefully tuned to the ensemble and instruments’ natural resonances. • Dynamics are often controlled and gradual rather than dramatic. • Emphasize ensemble listening so ornaments interlock without obscuring the melody.When vocal material is included, use Naxi language or local thematic content tied to place, ritual, and community memory. Even purely instrumental pieces should feel connected to ceremonial or narrative intent through pacing and timbre.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)