Mechanical music is music produced by self-playing instruments in which the score is encoded mechanically and reproduced without a live performer at the moment of sound. Typical media include pinned cylinders and discs (music boxes and musical clocks), pinned barrels (barrel organs), perforated paper rolls (player pianos and orchestrions), and punched book or card systems (fairground band organs).

Rather than defining a single musical style, mechanical music is a performance medium that historically rendered whatever repertoire was popular or practical for its machines: marches, waltzes, polkas, operatic potpourris, hymns, salon pieces, and, later, ragtime and light classics. Its hallmark is a precisely repeatable, often highly articulated execution that can sound charmingly clockwork or dazzlingly virtuosic, depending on the mechanism and arrangement.

Mechanical music flourished in public and domestic settings—on streets and fairgrounds, in dance halls, parlors, and clock cabinets—serving entertainment, dance, signaling, and timekeeping functions. It also inspired 20th‑century composers who explored automation, extreme complexity, and the aesthetic of the machine itself.

Early self-playing instruments existed well before the modern era, from ancient programmable water organs to medieval carillons. The direct ancestors of the genre emerged in the late 18th century in Switzerland, where watchmaking skill and miniature mechanics produced musical clocks and cylinder music boxes in the Jura region (notably around Sainte-Croix). These encoded melodies on pinned cylinders that plucked tuned metal teeth.

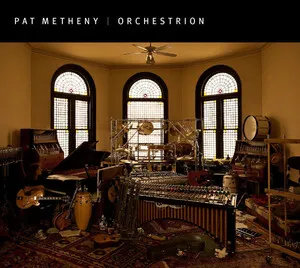

The 1800s saw rapid diversification and industrialization. Barrel organs and street organs brought portable mechanical music into public life, while salon music boxes and orchestrions entertained at home and in cafés. By the late 19th century, perforated paper rolls enabled player pianos (pianolas) and sophisticated orchestrions with selectable registrations and dynamics, vastly expanding repertoire and fidelity. Fairground and dance hall band organs, using punched books or large rolls, provided loud, festive music for carousels and public amusements.

Mechanical instruments rendered the era’s popular forms—waltzes, polkas, marches, opera and operetta selections, salon miniatures, hymns, and later ragtime—arranged to fit each machine’s scale, articulation, and register constraints. Arrangers exploited the uncanny precision and repeatability of mechanisms, sometimes creating virtuosic textures impractical for human hands.

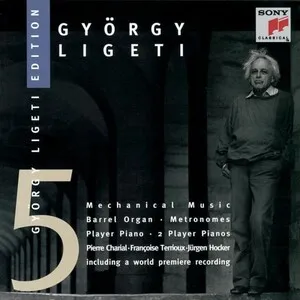

In the 20th century, composers turned the medium into a creative tool. George Antheil’s Ballet Mécanique used player pianos and mechanical percussion to celebrate—and critique—machine age aesthetics. Igor Stravinsky collaborated with pianola roll makers, and Conlon Nancarrow’s studies for player piano explored rhythmic complexity and tempo relationships beyond human performance. György Ligeti’s Poème Symphonique for 100 metronomes highlighted the sonic poetics of simple machines set in motion.

Museums, private collections, and specialist restorers maintain historic instruments, while contemporary builders and software emulations keep the sound alive. Mechanical music’s encoded performance, precise repetition, and modular registration presaged ideas in sequencing, step programming, minimal and process music, and the machine timbres embraced by industrial and techno scenes.

Decide on the target instrument type, because it determines constraints and possibilities:

• Music box or musical clock: limited pitch set, short decay, mainly melody with simple accompaniment. • Barrel organ or fairground organ: multiple ranks (flutes/reeds), fixed registrations, strong attack; ideal for marches, waltzes, and polkas. • Player piano (pianola): wide range, rapid figurations, polyrhythms and tempo can exceed human feasibility. • Orchestrion: organ-like with percussion and registers; think in blocks and registrations.