Your digging level

Description

Malhun (also spelled Melhoun) is a tradition of sung vernacular poetry from Morocco, performed in Moroccan Arabic (Darija) to refined, Andalusi-influenced melodic modes and measured rhythmic cycles.

It takes the form of lengthy qasidas (odes) built on monorhyme and strophic design, typically featuring a recurring refrain (harba) answered by a responsive chorus. A small orchestra—centered on oud, kamanja (violin), and frame/goblet drums—supports a lead vocalist whose ornate, melismatic delivery and narrative diction bring the text’s imagery, satire, devotion, or romance to life.

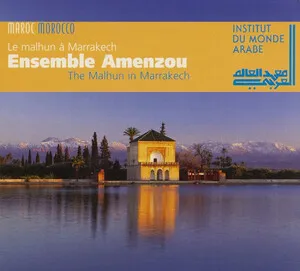

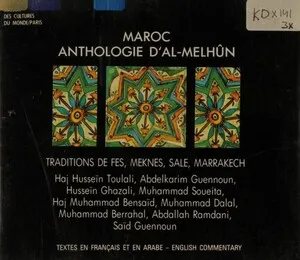

Rooted in urban craft guilds and Sufi circles of cities like Meknes, Fez, Marrakesh, and Tafilalt/Sijilmassa, malhun bridges classical Arab poetics with local musical aesthetics. Its performance style balances literary sophistication with popular accessibility, making it both a repository of Moroccan cultural memory and a living stage art.

History

Malhun emerged in Morocco during the 1500s–1600s, as urban poets and artisans adapted classical Arabic poetic forms into Darija, the everyday Moroccan Arabic. The genre’s melodic and rhythmic scaffolding drew heavily from Andalusian musical practice that had flourished across the Maghreb after the post‑Andalus dispersions. Early qasidas crystallized around monorhyme, strophic layouts, and refrains, enabling long-form storytelling and devotional praise.

By the 1700s–1800s, malhun was deeply embedded in the social life of Meknes, Fez, Marrakesh, and Tafilalt. Poets associated with craftsman guilds and Sufi zawiyas composed qasidas on love, ethics, satire, and prophetic praise. Ensembles adopted Andalusi modes (tubū‘) and measured rhythmic cycles, while performance protocol solidified around a lead “shaykh” and a chorus that carried the harba (refrain). Iconic poet‑figures such as Sidi Kaddour El Alami and Abdelaziz al‑Maghraoui set enduring textual and musical standards.

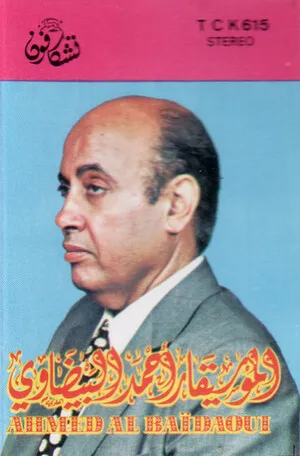

With the advent of recording and radio, malhun moved from private salons to national stages. Star vocalists—supported by small orchestras—fixed a shared repertoire and stylistic norms for intonation, ornamentation, and pacing. This period also saw Jewish‑Moroccan artists record malhun widely, extending its reach across North Africa and the diaspora. Conservatories and cultural associations began documenting qasidas and training new generations of performers.

Today, malhun remains a prestigious poetic‑musical art presented at festivals, cultural centers, and on broadcast media. Associations commission new qasidas alongside canonical works, and collaborations with Andalusi orchestras are common. While firmly traditional, the genre continues to inform broader Maghrebi song aesthetics and occasionally intersects with modern arrangements without losing its core poetic and modal identity.