Your digging level

Description

Kai is a traditional style of overtone (throat) singing from the Altai–Sayan region, especially the Altai Republic in Siberia.

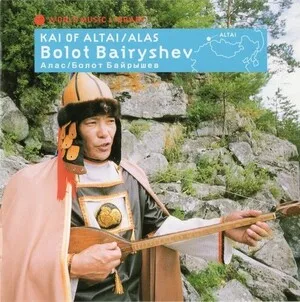

Rooted in shamanic cosmology, kai emphasizes a very low fundamental with clearly articulated upper partials that outline pentatonic figures. Performers (kaichi) often accompany themselves on long‑neck lutes such as the topshur and frame drums, chanting epics and nature invocations that are believed to communicate with the land, animals, and ancestral spirits.

While closely related to Tuvan and Mongolian throat‑singing practices, kai retains distinctive Altaian timbres, epic‑narration delivery, and a repertoire that moves fluidly between recitative storytelling and sustained, droning vocal textures.

History

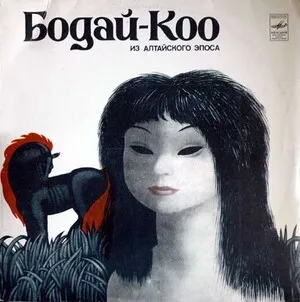

Kai likely predates written records, emerging among Turkic Altaian peoples as a sacred vocal practice tied to animist–shamanic ritual. The performer (kaichi) used a low, buzzing fundamental and shaped overtones while narrating origin myths, heroic cycles, and landscape songs, treating the voice as a conduit to nature and the spirit world.

Ethnographers and travelers in the 19th century began describing Kai‑like throat singing in the Altai–Sayan area. In the Soviet era, regional ensembles and conservatories documented epic repertoires and techniques; notable kaichi such as Alexei Kalkin helped codify performance approaches while keeping the oral lineage alive.

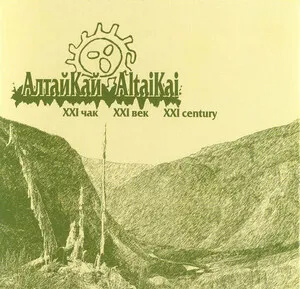

After the 1990s, ensembles from the Altai Republic professionalized the style for stage and recording. Groups like Altai Kai toured internationally, taught workshops, and released albums that foregrounded kai’s low‑register drones, overtone melodies, and epic narration. Today, kai appears both in traditional settings (rituals, community festivals) and in cross‑cultural collaborations, influencing world‑fusion and experimental vocal scenes.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)