Jewish music is a broad, diasporic family of musical practices tied together by Jewish religious life, languages, and communal rituals. It encompasses liturgical chant (nusach and cantillation), para-liturgical song (piyyut, nigunim), and a wide spectrum of folk and popular repertoires that grew within Jewish communities across Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia.

Across its branches, Jewish music is characterized by modal systems (from synagogue nusach to Middle Eastern maqam), richly ornamented, melismatic vocal lines, responsorial and communal singing, and repertoire in Hebrew alongside Jewish languages like Yiddish, Ladino (Judeo-Spanish), and Judeo-Arabic. Instrumentation and rhythm reflect local host cultures: klezmer ensembles use clarinet, fiddle, tsimbl/cimbalom, and accordion, while Sephardi and Mizrahi traditions favor oud, qanun, darbuka/riqq, and frame drums. Weddings, life-cycle rituals, Sabbath/holiday services, and storytelling all provide contexts where music functions as a vehicle for memory, devotion, joy, and communal identity.

Jewish musical practice traces back to Ancient Israel, where Temple worship featured Levitical singing, trumpets, and psaltery/lyre traditions. After the destruction of the Second Temple (70 CE), synagogue chant (nusach) and biblical cantillation (taʿamei ha-mikra) became the primary sacred frameworks. Early piyyutim (Hebrew liturgical poems) spread between Late Antiquity and the early medieval period, shaping a devotional, text-centered musical culture.

As Jews dispersed, their music absorbed and interacted with host traditions:

• Ashkenazi (Central & Eastern Europe): Parish church modes, Gregorian/Byzantine spheres, and Slavic/Romani folk idioms filtered into synagogue chant and the instrumental wedding tradition that became klezmer. • Sephardi (Iberia → Mediterranean/North Africa/Ottoman world): Judeo-Spanish (Ladino) romansas and coplas married Andalusian, Ottoman, and Maghrebi modal practice and instrumentation. • Mizrahi (Middle East, North Africa, Central Asia): Hebrew and Judeo-Arabic piyyutim aligned with Arabic/Turkish/Persian maqam practice; Bukharan and Yemenite communities developed distinct vocal timbres and rhythmic profiles.The rise of virtuoso hazzanut (cantorial art) in Europe brought operatic projection and elaborate melisma into synagogue settings. Klezmer kapelyes evolved as professional bands for weddings and communal events, standardizing dance forms (freylekhs, bulgars, horas) and improvisatory ornamentation (krekhts, dreydlekh). In the Ottoman/Mediterranean orbit, Jewish poets and singers participated in multi-ethnic art-music salons and devotional circles.

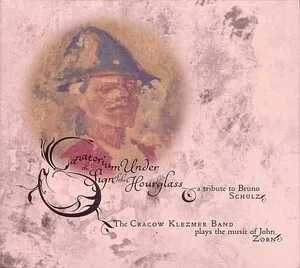

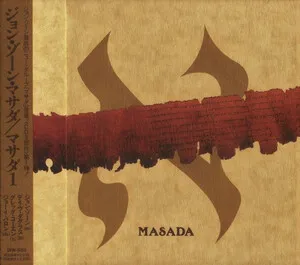

Migration to the Americas and Palestine/Israel reshaped Jewish soundscapes. Yiddish theatre and American klezmer flourished before WWII, while the Holocaust devastated communities and disrupted transmission. Post-1948, Israeli song and dance synthesized Ashkenazi, Sephardi, and Mizrahi sources. In the late 20th century, revival movements (klezmer renaissance, Ladino revivals) and new sacred song (Carlebach, Reform/Conservative folk-liturgical repertoires) renewed communal singing.

Today, Jewish music thrives across genres: Hasidic pop, cantorial fusion, Sephardi/Mizrahi piyyut ensembles, Israeli rock/pop, and global collaborations. Artists blend maqam with jazz, klezmer with funk, and liturgical texts with electronic production, extending an ancient, text-driven tradition into new stylistic territories.