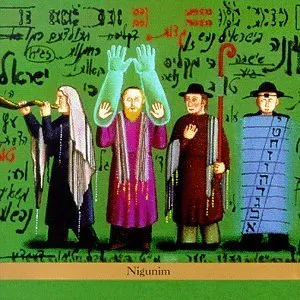

Hasidic music is the devotional and communal song tradition of Hasidic Judaism, centered on nigunim—repetitive, often wordless melodies intended to elevate the soul and intensify prayer. It spans meditative, slow pieces (devekut nigunim) and exuberant dance tunes (simcha nigunim) sung at tishes, weddings, and holidays.

Historically shaped in Eastern Europe, Hasidic music blends Jewish liturgical modes and cantorial ornamentation with local folk and dance idioms. Performances are typically communal and participatory—built on call-and-response, cyclical repetition, and gradual emotional build-up—aimed not at virtuosity but at spiritual ascent and collective joy. In the modern era it also encompasses a popular "Hasidic pop" stream that adapts its melodic language to contemporary band formats.

Hasidic music took shape alongside the rise of Hasidic Judaism in the mid‑18th century in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (especially present‑day Ukraine). Early leaders such as the Baal Shem Tov emphasized heartfelt prayer and song as pathways to devekut (cleaving to the Divine). The nigun—cyclical, easily memorizable, often wordless—became the signature musical form, designed to move large groups collectively from inward focus to spiritual ecstasy.

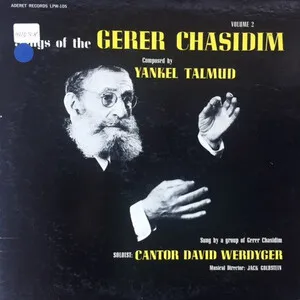

As Hasidism spread, courts (e.g., Chabad‑Lubavitch, Breslov, Karlin‑Stolin, Modzitz) cultivated distinct musical aesthetics. Cantorial expressivity and Ashkenazi liturgical modes mingled with regional Slavic and Central/Eastern European folk dances, marches, and waltzes. The Modzitz dynasty became renowned for complex, through‑composed nigunim; Karlin‑Stolin favored forceful, declamatory congregational tunes; Chabad emphasized layered, contemplative melodies.

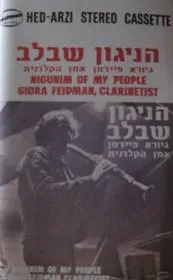

Following upheavals and migration, Hasidic communities reestablished in North America and the Land of Israel. Field collectors and court musicians began notating and recording repertoires (e.g., Chabad’s Nichoach series). From the 1960s onward, figures like Shlomo Carlebach popularized Hasidic melodic language beyond Hasidic circles, marrying nigun motifs to simple Hebrew texts and guitar-led song forms. In Israel, festivals and media exposure helped formalize a "Hasidic song" platform, while in the U.S., orchestral wedding bands and studio producers adapted nigunim for contemporary arrangements.

Today Hasidic music thrives both in traditional settings (tish, prayer, lifecycle events) and as a commercial genre often labeled "Hasidic pop" or Orthodox pop. Singers and arrangers (e.g., Mordechai Ben David, Avraham Fried, Yaakov Shwekey, Lipa Schmeltzer, Benny Friedman, Beri Weber, and composers like Yossi Green) fuse classic nigun contours with modern harmony, rhythm sections, and brass. Despite stylistic evolution, core traits remain: communal participation, repetitive form, modal color, and the goal of spiritual uplift.