Ukrainian folk music is a broad corpus of rural vocal and instrumental traditions shaped by village life, seasonal rituals, and the Cossack epic heritage. It is marked by striking vocal timbres (including the open-throated “white voice”), flexible modal harmony, and a balance between solo declamation and tight ensemble polyphony.

Typical forms include ritual carols (koliadky) and New Year songs (shchedrivky), spring songs (vesnianky), Kupala Night repertoire, harvest and wedding cycles, lyrical ballads, and the epic dumy sung by kobzars and bandurists. Dance genres such as hopak, kozachok, kolomyjka, and hutsulka feature driving duple meters, sudden accelerations, and ornamental violin or tsymbaly lines.

Characteristic instruments include the bandura and kobza (plucked lutes), sopilka (end-blown flute), tsymbaly (hammered dulcimer), trembita (alpine horn), basolya (folk cello), violin, and frame drums (buben). Melodies often use Dorian, Aeolian, and Mixolydian modes, drones, heterophony, and parallel thirds, yielding a sound that can be both exuberant and contemplative.

Ukrainian folk music crystallized around village ritual cycles and the Cossack era’s epic tradition. Blind bards—kobzars and lirnyky—sang historical dumy accompanied by bandura, kobza, or hurdy-gurdy (lira), preserving chronicles of battles and moral tales in free rhythm and modal chant-like melodies. Parallel to this epic line ran a rich body of seasonal and family-ceremonial songs whose polyphonic textures and white-voice timbres reflected communal village singing.

In the 1800s, scholars and composers such as Mykhailo Maksymovych, Filaret Kolessa, and Mykola Lysenko collected and published folk songs, harmonized them for choirs, and used them as thematic material in art music. This ethnographic movement codified regional repertoires (Hutsul, Boyko, Lemko, Polissia, Podillia) and secured the bandura tradition as a national symbol. Printed anthologies and urban concerts brought village repertoire to educated audiences.

The 20th century brought state ensembles and staged folklore. The Veryovka Ukrainian Folk Choir (founded 1943) popularized grand choral arrangements and choreographed suites, while the “Dumka” Choir (founded 1919) helped canonize arranged folk polyphony. Although authentic village styles continued to exist, official taste favored polished, orchestrated versions. Simultaneously, diaspora communities and fieldworkers preserved raw village singing and kobzar practices outside state frameworks.

After 1991, there was a surge in fieldwork, archival projects, and community ensembles dedicated to authentic performance practice (e.g., Drevo, Bozhychi). Folk festivals, local museums, and university programs supported regional styles, while younger artists began to fuse folk with jazz, rock, and electronic music. Reconstruction of rituals (calendar cycles, wedding customs) and renewed interest in the bandura restored depth and visibility to the tradition.

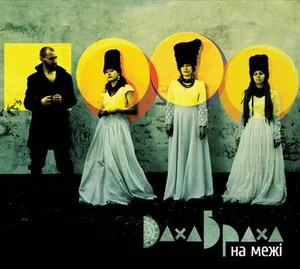

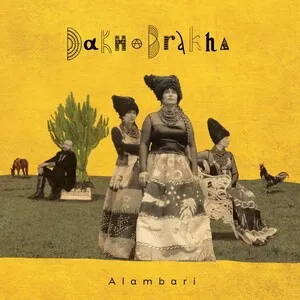

Following the 2014 Revolution of Dignity and Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, folk music became a powerful vehicle for cultural identity and resilience. Global-facing groups like DakhaBrakha brought Ukrainian polyphony and rhythms to world-music stages, while digital archives and social media amplified field recordings and teaching. Today, Ukrainian folk thrives both in historically informed village styles and in cutting-edge fusions with electronic, rock, and experimental idioms.