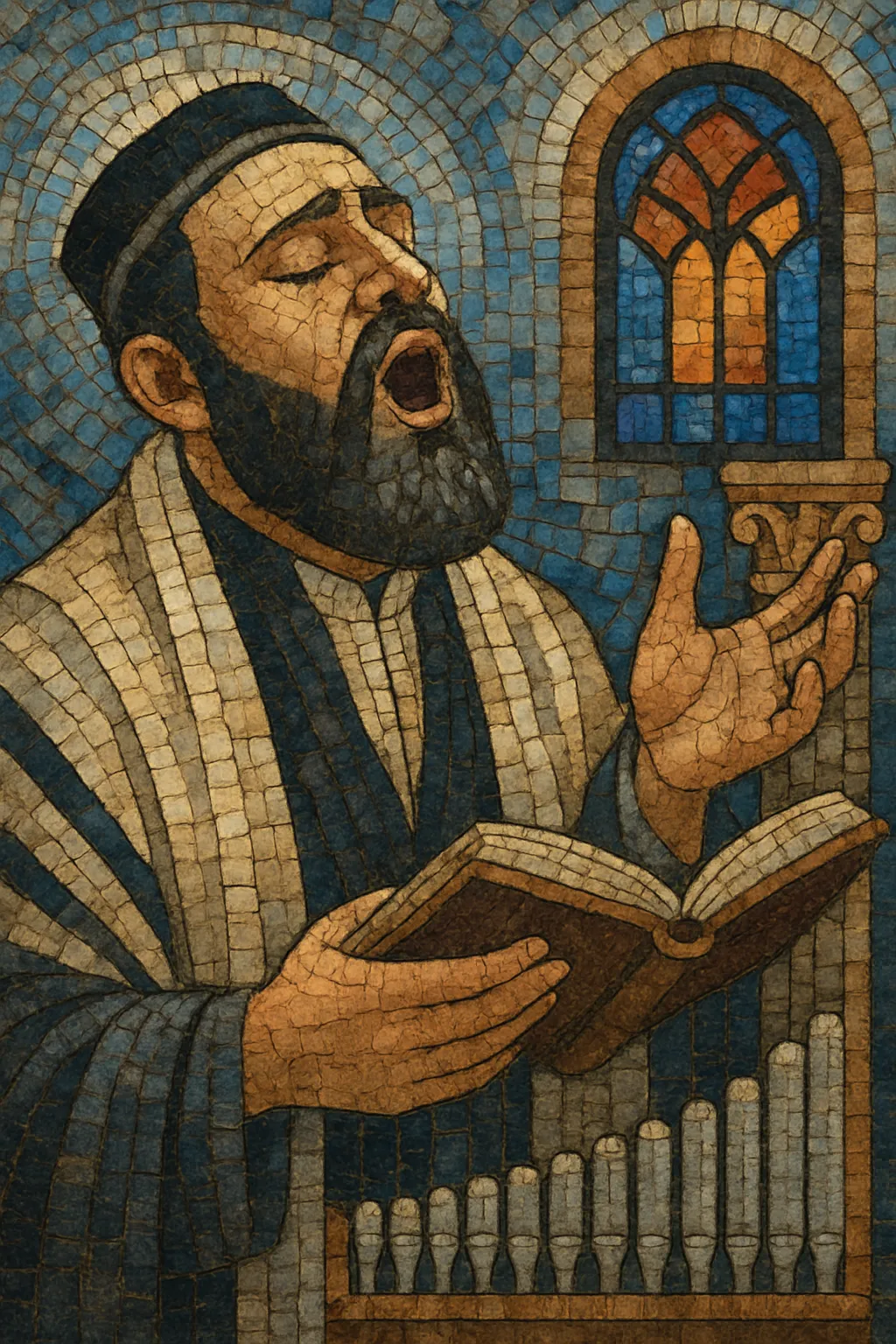

Ashkenazi cantorial music is the liturgical vocal art of the Ashkenazi Jewish synagogue, led by a trained cantor (hazzan). It is built on the nusach—the modal and motivic system that encodes time, place, and liturgical function—together with biblical cantillation patterns and a highly ornamented, improvisatory delivery.

Its sound world features melismatic lines, free-rubato recitative, dramatic leaps, sob-like timbral ornaments called krekhts, and characteristic modes such as Ahavah Rabbah (Phrygian dominant), Adonai Malach (a major/Mixolydian family), and Magein Avot (minor). Performances range from unaccompanied solo prayer to responses with a choir and, in some Western and modern settings, organ or small ensemble. The texts are in Hebrew and Aramaic, and the music serves the liturgy rather than concert display, even when it reaches great virtuosity.

Ashkenazi cantorial practice descends from the ancient Jewish chant traditions transmitted orally in synagogues, shaped by biblical cantillation and communal prayer modes (nusach). As Ashkenazi communities consolidated in Central and later Eastern Europe, local melodic dialects and performance customs coalesced. By the 1700s, a professional class of hazanim (cantors) emerged, formalizing an art that balanced improvisation with established modal motifs tied to the liturgical calendar.

In the 1800s, the virtuoso style known as hazzanut flourished across the Polish–Lithuanian territories, Galicia, and the Russian Empire. Synagogue choirs became common, and in some Western congregations organs were introduced. Star cantors developed large followings, integrating operatic projection and European classical phrasing while remaining grounded in nusach. By the early 1900s, the so‑called "Golden Age" produced iconic cantors whose 78‑rpm records spread the style internationally.

Large-scale Jewish migration to the Americas brought leading cantors to New York and other urban centers. Commercial recordings, radio appearances, and concert hall performances broadened audiences. While some communities maintained strictly unaccompanied prayer, others embraced choral arrangements and concertized presentations of sacred repertoire. The catastrophic losses of European Jewry in the Holocaust severed many local traditions, but recordings and émigré teachers kept the art alive.

After World War II, cantorial music adapted to diverse synagogue movements and acoustics, from traditional Eastern European davening to Westernized services with organ and choir. Cantorial schools codified technique and pedagogy, and archival restorations revived historic recordings. Contemporary hazanim blend classic improvisatory practice with historically informed performance, choral composition, and occasional crossover projects, all while preserving the primacy of text, mode, and liturgical function.