Sephardic music is the musical tradition of the Sephardi Jews, rooted in medieval Iberia and carried across the Mediterranean after the 1492 expulsion.

It is best known for its Judeo‑Spanish (Ladino) repertory of romances (narrative ballads), coplas, and devotional songs, sung in distinctive modal scales shared with Arabic, Ottoman, and North African art and folk musics. Typical performance is voice‑led and ornamented, supported by instruments such as oud, qanun, violin, guitar, and frame drums, with rhythms ranging from simple 2/4 to additive meters like 9/8 (karsilama) and 10/8 (samai).

Across centuries, local diasporas (Ottoman Balkans, Turkey, Greece, Morocco, Algeria, the Levant) shaped regional variants—some more Ottoman‑classical in color, others more Maghrebi—while preserving the core Iberian poetic and melodic inheritance.

Sephardic music began among Jewish communities in medieval Spain and Portugal, drawing on courtly and popular Iberian song (romances and cantigas) while absorbing modal practice from the broader Andalusian milieu. Much of the repertory was transmitted orally, with texts in early Judeo‑Spanish and Hebrew.

Following the 1492 Alhambra Decree and subsequent expulsions, Sephardi Jews dispersed across the Ottoman Empire (Thessaloniki, Istanbul, Izmir, Sarajevo), North Africa (Tetouan, Tangier, Oran), and the Levant. In Ottoman lands the repertory interacted with makam‑based Ottoman classical and urban folk styles; in the Maghreb it intertwined with Andalusian‑Maghrebi traditions. Distinct dialects (Ladino, Haketía) and local instruments (oud, qanun, violin, ney; bendir, riq, darbuka) colored performance while preserving Iberian poetic forms.

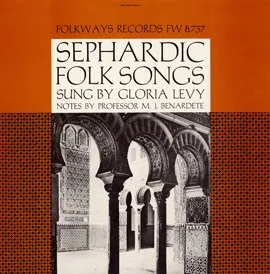

Early 20th‑century artists such as Haïm Effendi recorded Judeo‑Spanish songs in Istanbul, fixing variants that had been primarily oral. Later, ethnomusicologists and ensembles documented surviving repertoires across Turkey, Greece, the Balkans, and North Africa, while immigrant communities in the Americas and Israel sustained liturgical and paraliturgical traditions.

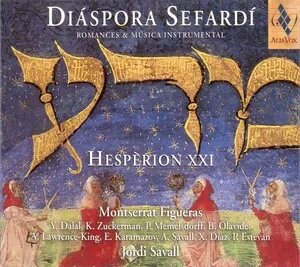

From the 1970s onward, early‑music and world‑music movements fueled renewed interest. Artists and ensembles (e.g., Jordi Savall & Hespèrion XXI, Flory Jagoda, Yasmin Levy) revived romances and coplas with historically informed and cross‑cultural arrangements. Today, Sephardic music thrives in concert, synagogue, and community settings, balancing archival authenticity with contemporary creativity.