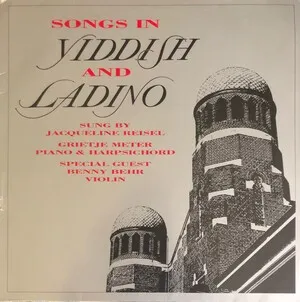

Ladino folksong is the secular song tradition of the Sephardic Jews, sung in Judeo‑Spanish (Ladino/Djudeo‑Espanyol) that preserves medieval Iberian Spanish alongside Hebrew and regional loanwords. The repertoire includes romances (narrative ballads), kantikas (lyric songs), coplas (strophic songs), lullabies, wedding and life‑cycle songs.

Musically, it blends medieval Iberian balladry with modal aesthetics and rhythms absorbed across the Sephardic diaspora in the Ottoman Balkans, Anatolia, North Africa, and the Eastern Mediterranean. Typical modes include Hijaz/Phrygian‑dominant and Nahawand (harmonic minor), with ornamented melodies and flexible intonation that may reflect local makam practice. Rhythms often use asymmetric meters (9/8, 7/8) alongside simple duple/triple. Traditional accompaniment features oud, qanun, violin, guitar, darbuka/frame drum, and sometimes accordion; historically many songs were transmitted a cappella, especially in women’s domestic and communal contexts.

Ladino folksong descends from the medieval Spanish ballad (romance) tradition cultivated by the Sephardic Jews in late medieval Iberia. Many core texts and tunes crystallized between the 14th and 15th centuries, using strophic forms, narrative storytelling, and melodies related to the broader Iberian folk idiom.

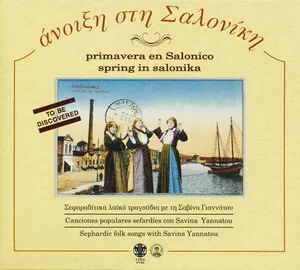

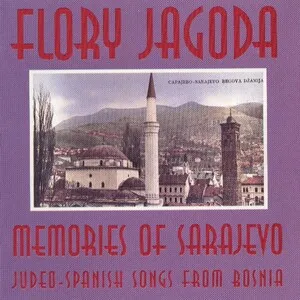

Following the 1492 Alhambra Decree and subsequent expulsions, Sephardic communities resettled across the Ottoman Empire (Salonika/Thessaloniki, Istanbul, Sarajevo, Izmir, Rhodes) as well as in North Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia) and the Levant. In each locale, the repertory absorbed local musical traits—makam/modal practice, asymmetric meters, and instruments such as oud, qanun, and darbuka—while preserving archaic Iberian language and ballad narratives.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, folklorists and cantors began notating and collecting Sephardic songs. Early commercial recordings from Salonika, Istanbul, and North Africa capture regional variants. Urban café and salon cultures also influenced accompaniment practices and performance style.

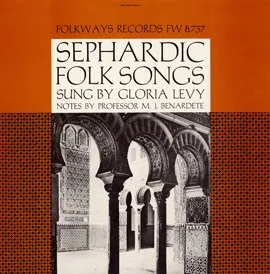

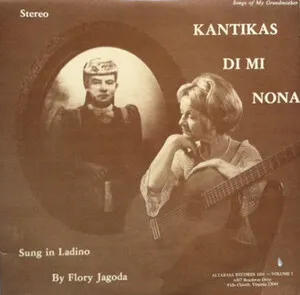

The Holocaust devastated major Ladino‑speaking centers (notably Salonika). Post‑war, tradition bearers in the diaspora—especially families from the Balkans and the Eastern Mediterranean—transmitted songs orally. From the 1960s onward, ethnomusicologists and performers (field collectors, early‑music ensembles, and singer‑song interpreters) spurred a revival, recording classic romances, wedding songs, and lullabies.

Today, Ladino folksong thrives through heritage transmission, archival releases, and new arrangements that respectfully blend flamenco, Balkan, Middle Eastern, or jazz colors. Artists balance historical performance practice with creative re‑imagining, while community projects help sustain the Judeo‑Spanish language and its song culture.