Your digging level

Description

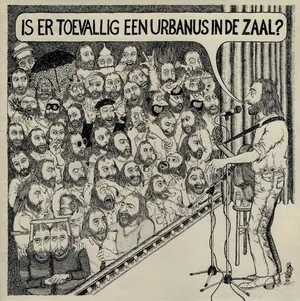

Dutch cabaret is a popular form of musical-theatrical comedy from the Netherlands that blends songs, monologues, sharp satire, and intimate storytelling. Emerging in the fin‑de‑siècle era as a localized offshoot of French and German cabaret, it prioritizes wordcraft, topicality, and direct conversation with the audience.

Traditionally performed in small theaters with piano or small-ensemble accompaniment, Dutch cabaret ranges from playful and light to piercingly political and poignant. Performers often alternate between sung couplets and spoken "conference" segments, weaving humor with social commentary and personal reflection—hallmarks that distinguish it from broader variety or revue formats.

History

Dutch cabaret took shape in the 1890s under the influence of Parisian and German cabaret, as well as local theater traditions. Early practitioners adapted the intimate, café-based format—songs and couplets interspersed with witty monologues—into Dutch language and contexts. The emphasis on concise song forms, wordplay, and social observation quickly resonated with urban audiences in Amsterdam and beyond.

Between the wars and into the postwar period, the genre matured in theaters and on emerging broadcast media. Piano-led accompaniment and small ensembles remained standard, while the lyrical focus broadened from urbane satire to include reflective pieces and narrative sketches. Postwar reconstruction and shifting social values gave performers fertile ground for topical humor and nuanced sentiment.

The mid‑20th century canonized cabaret as a quintessentially Dutch artform. Iconic solo performers refined the blueprint: intimate theaters, meticulously crafted lyrics, and a balance of levity and melancholy. The tradition of the year‑end "conference"—a satirical look back on the year—took hold and became a cultural ritual, helping to link cabaret with civic life and collective memory.

Television expanded cabaret’s reach, while a new generation infused stronger political bite, experimental staging, and edgier humor. Duo and ensemble formats emerged alongside solo acts, and performers pushed boundaries of taste and form. The genre increasingly spoke to social movements, broadcasting rooms’ immediacy to living rooms while retaining its crafted lyrical core.

As Dutch society diversified, so did cabaret’s voices and topics: identity, migration, gender, and globalization entered the repertoire. Stylistically, artists mixed chanson, pop, jazz, and even hip‑hop cadences with classic cabaret delivery. Theater schools and dedicated kleinkunst programs professionalized training, and touring circuits kept the club‑like intimacy alive.

Today, Dutch cabaret thrives across theaters, television, streaming, and podcasts. It remains rooted in carefully wrought Dutch‑language texts, audience rapport, and flexible formats—song, spoken word, and satire—while renewing itself with multimedia staging, collaborative bands, and cross‑genre influences.