Your digging level

Description

Cajun music is the traditional dance and song tradition of the French-speaking Cajuns of southwest Louisiana. It is typically driven by diatonic button accordion and fiddle, supported by guitar, triangle (tit-fer), and, in modern bands, bass, drums, and steel guitar.

The repertoire centers on lively two-steps in 4/4 and tender waltzes in 3/4, with melodies that lean on major and mixolydian modes, blue notes, and fiddle double-stops. Vocals—often in Cajun French—carry themes of love, loss, home, and community, delivered with a nasal, emotive timbre. The overall feel is simultaneously earthy, communal, and irresistibly danceable.

History

Cajun music traces to the Acadian settlers expelled from present-day Atlantic Canada in the mid-18th century and resettled in Louisiana. They brought French ballads and dance tunes that blended with Anglo-American fiddle traditions, Indigenous and African rhythmic sensibilities, and the broader folk culture of the Gulf Coast. By the late 19th century, a distinct regional dance music—built around fiddle-led two-steps and waltzes—had formed in rural southwest Louisiana.

The diatonic button accordion, arriving in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, became a hallmark, reshaping melody and harmony. Early recording pioneers such as Joe Falcon and Cleoma Breaux, Dennis McGee, and the Creole musician Amédé Ardoin documented the emergent style in the 1920s and 1930s. Their records standardized core repertoire, rhythms, and a call-and-response interplay between accordion and fiddle.

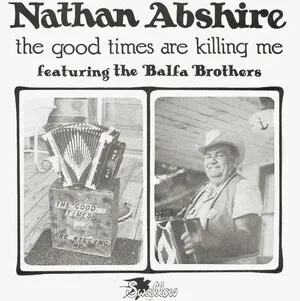

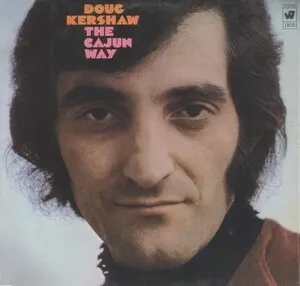

After WWII, amplification, drums, and steel guitar entered Cajun bands under the influence of country, honky-tonk, and Western swing. Artists like Iry LeJeune and Nathan Abshire helped revive the prominence of the one-row accordion, balancing modern dancehall energy with traditional aesthetics. This era cemented the two-step/waltz dialectic and produced many of the genre’s most enduring standards.

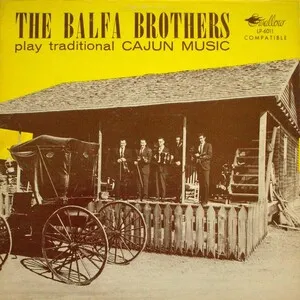

The 1960s–70s folk revival and cultural activism (e.g., Dewey Balfa and Festivals Acadiens) revitalized pride in Cajun language and music. Touring groups such as BeauSoleil carried the style to international stages, while younger artists fused tradition with contemporary production. Today, Cajun music thrives in dancehalls and festivals, coexisting with closely related Creole forms (e.g., zydeco) and influencing American roots music at large.

How to make a track in this genre

Use a one-row diatonic button accordion (often in C) and a fiddle as co-leads. Add guitar for rhythm (boom-chuck strums), triangle (tit-fer) for a metallic backbeat, and, in modern settings, upright/electric bass, drums, and sometimes steel guitar. Keep the accordion’s push-pull phrasing central to the groove.

Alternate between two-steps (4/4) and waltzes (3/4). Two-steps typically sit around 100–130 BPM with a driving, lightly swung feel; waltzes around 60–90 BPM with a lilting sway. Common structures include AABB for instrumentals and verse–chorus for songs, with instrumental turnarounds between vocal sections.

Favor major and mixolydian modes with occasional blues inflections (flat 3, flat 7). Harmony is primarily I–IV–V with simple, strong cadences. Let the accordion outline chords through bass-chord patterns while the fiddle uses double-stops, drones, and slides to enrich texture. Melodies should be singable and dance-forward, often answering the accordion with the fiddle (and vice versa).

Write in Cajun French when possible, focusing on themes of love, heartbreak, home, and communal life. Use a nasal, emotive delivery with occasional call-and-response. Keep verses concise and memorable to encourage dancing and crowd participation.