Your digging level

Description

Balinese music refers to the rich ensemble and vocal traditions of the island of Bali, Indonesia, best known for its vibrant bronze gamelan orchestras, tightly interlocking rhythms, and brilliant dynamic contrasts.

It encompasses many ensemble types—such as gong kebyar, gender wayang, angklung, jegog, and beleganjur—each tied to specific social functions including temple ceremonies, dance-drama, processions, and modern stage performance. Balinese tuning systems (sléndro- and pélog-derived local modes) are uniquely realized through paired instruments tuned slightly apart to create a characteristic acoustic “shimmer” (ombak).

The music’s hallmark techniques include rapid interlocking figuration (kotekan), bold sectional contrasts (kebyar “explosions”), and drum-led cues (angsel) that synchronize music and dance. While deeply rooted in ritual and community life, Balinese music has also become a global influence, informing modern composition and cross-cultural collaborations.

History

Balinese musical culture coalesced between the 1400s and 1600s as Hindu–Javanese courtly and temple traditions took root following Majapahit-era migrations from Java. Bronze gamelan orchestras and sung forms associated with ritual, theater, and poetry (e.g., kakawin) were cultivated in palaces (puri) and village banjar, embedding music in ceremonies and cycle-of-life events.

Over centuries, Bali developed distinct gamelan types with specialized roles: gender wayang for shadow theater (wayang kulit), gambuh ensembles for old court dance-drama, angklung for ceremonial processions, and large gong sets (e.g., gong gede) for temple festivals. Each ensemble’s tuning, instrumentation, and repertoire reflect localized aesthetics and functions.

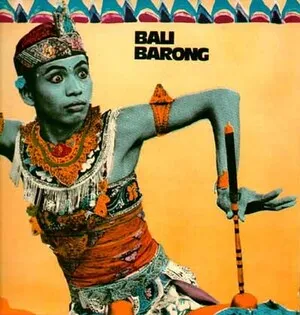

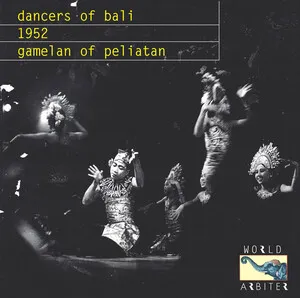

In the early 20th century—especially after the upheavals of 1906–1908—North Bali communities forged a new, virtuosic style: gong kebyar. Characterized by sudden dynamic contrasts (kebyar), rapid interlocking kotekan, and dazzling showpieces, it quickly spread across the island. Dancer I Mario (I Ketut Mario) helped define modern dance-musical idioms (e.g., Kebyar Duduk). This period also saw ensembles touring abroad (e.g., Paris, 1931), introducing global audiences to Balinese performance.

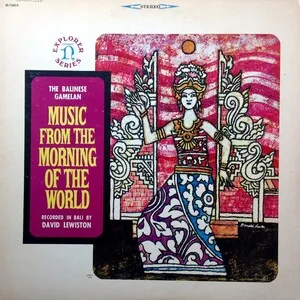

From the 1930s onward, scholars and composers such as Colin McPhee documented and drew inspiration from Balinese music, catalyzing its impact on Western composition and later minimalist aesthetics. The 1930s also saw the staging of kecak—a choral, trance-derived spectacle—by Wayan Limbak and Walter Spies, which became emblematic of Balinese stage culture.

Post-independence, schools and arts institutes (later ISI Denpasar) formalized training while community banjar maintained grassroots vitality. New ensembles and forms—jegog (bamboo gamelan), processional beleganjur, and innovative gong kebyar compositions—expanded the palette. From the late 20th century to today, Balinese composer-performers have continued to innovate, creating new tunings, ensembles, and intercultural works while sustaining temple-based performance cycles.