Your digging level

Description

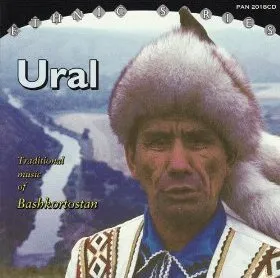

Volga–Ural folk music is an umbrella term for the traditional musics of the Volga and Ural regions of Russia, especially those of the Turkic (Tatar, Bashkir) and Uralic/Finno‑Ugric (Mari, Mordvin/Erzya & Moksha, Udmurt, Komi) peoples.

It is characterized by a blend of Turkic modal, often pentatonic or maqam‑tinged melodies and Uralic multipart or heterophonic vocal textures, frequent drones, and clear dance rhythms. Signature timbres come from end‑blown flutes (qurai/kurai), jaw harps (kubyz), frame drums, and later the garmon (button accordion), with local instruments such as the Mari shuvyr (bagpipe) and plucked lutes retained in some repertoires.

Songs range from epic narratives and ritual laments to circle‑dance refrains and pastoral love songs, typically sung in Tatar, Bashkir, Erzya, Moksha, Mari, Udmurt, Komi, and Russian. The result is a vivid, rhythmically buoyant regional sound that bridges Islamic and Orthodox cultural spheres and fuses steppe song with forest polyphony.

History

The Volga–Ural region has long been a crossroads where Turkic, Uralic/Finno‑Ugric, and East Slavic cultures met. Traditional repertoires formed around village ritual (weddings, harvests, calendrical feasts), epic and historical songs, work chants, and dance tunes. Turkic groups (Tatar, Bashkir) contributed modal, often pentatonic or maqam‑inflected melodies and instruments like the qurai (end‑blown flute) and kubyz (jaw harp). Uralic peoples (Mari, Mordvin/Erzya & Moksha, Udmurt, Komi) emphasized multipart textures, drones, and tight‑knit women’s ensemble singing with antiphony and heterophony.

From the 1800s, imperial and early ethnographers began notating and collecting songs, while urban ensembles adapted rural material for stages in Kazan, Ufa, Yoshkar‑Ola, Saransk, Izhevsk, and Syktyvkar. The garmon (button accordion) and concert formats entered village life, standardizing some dance rhythms and tonal centers without erasing local modalities and languages.

Under the USSR, state song‑and‑dance ensembles professionalized local traditions, arranging polyphonic choral parts, adding orchestral accompaniment, and curating "stage folklore" repertoires for domestic and international tours. While ideological filtering occurred, institutional support preserved costumes, languages, and instruments, and created large archives of recordings and field notes.

After 1991, language and heritage initiatives, festivals, and independent ensembles catalyzed a revival. Field‑based groups foregrounded authentic village styles, while crossover acts blended Volga–Ural material with rock, jazz, and electronic idioms. Eurovision‑era visibility (e.g., Udmurt grandmothers) and world‑music circuits introduced the region’s timbres and meters to global audiences.

Contemporary practice spans community ritual contexts, conservatory ensembles, and fusion projects. The core aesthetics—modal melodies, drones/heterophony, flexible speech‑driven phrasing, and propulsive circle‑dance rhythms—continue to define the sound even when paired with modern instrumentation.