Udmurt folk music is the traditional music of the Udmurt people, a Finno‑Ugric group living in the Volga‑Ural region of Russia. It is sung primarily in the Udmurt language and is closely tied to agrarian cycles, family life, and pre‑Christian ritual practices.

Musically, it favors narrow‑range melodies, heterophonic or unison group singing, and modal or pentatonic pitch collections. Ritual laments and lullabies tend toward free rhythm and flexible phrasing, while circle‑dance songs use steady duple meters with clear refrains. Typical timbres include bright, nasal vocal production with ornamental turns and slides.

Instrumentation ranges from archaic plucked zithers (such as local kantele/gusli‑type instruments often grouped under regional names) and jaw harp to later folk‑ensemble staples like button accordion (garmon), fiddle, and hand percussion. The music’s social function remains central: it is a living repertoire for weddings, seasonal festivals (such as spring celebrations), and communal dances.

Udmurt folk music arises from the daily and ritual life of the Udmurt people, with roots that long predate written documentation. Songs marked agricultural seasons, weddings, funerals, and community rites associated with traditional beliefs (including invocations of nature and ancestral spirits). Melodies were typically narrow in range, transmitted orally within families and villages, and performed in flexible, heterophonic textures.

Systematic collection began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as Russian and regional ethnographers recorded texts, tunes, and rituals across the Volga‑Ural region. This period preserved numerous variants of circle‑dance songs, laments, and lullabies, and documented the expansion of instrumental practice with violin and button accordion as they entered village ensembles.

During the Soviet period, folkloric material was curated for stage presentation. State ensembles and choirs arranged traditional melodies with standardized harmonies and choreographies, bringing Udmurt repertoires to concert halls and radio. While some ritual contexts diminished, staged folklore and school ensembles helped sustain language and song transmission.

Following the 1990s cultural revival, community ensembles, heritage festivals, and local scholars re‑centered village styles, dialect forms, and less formal performance practices. International visibility spiked when Buranovskiye Babushki, a group of village grandmothers from Udmurtia, showcased Udmurt songs to global audiences. Today, the tradition lives in parallel tracks: home‑and‑festival contexts that retain flexible, oral styles, and professional troupes that present amplified, choreographed versions for large stages.

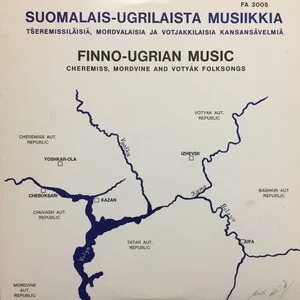

%20-%20Finno-Ugrian%20Music%20(Cheremiss%2C%20Mordvine%20and%20Voty%C3%A1k%20Folksongs)%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)