Mari folk music is the traditional music of the Mari people, a Finno‑Ugric ethnic group of the Volga–Ural region of present‑day Russia. It is primarily vocal, communal, and ritual in function, with songs tied to seasonal ceremonies, weddings, laments, and everyday work.

Typical performance practice features heterophonic unison (several voices singing the same melody with small, individual variations), call‑and‑response refrains, and narrow‑ranged modal melodies that can sound pentatonic or anhemitonic. Drones and sustained tones are common, either sung or provided by instruments.

Core instruments include the local zither (often referred to as a kusle/gusli‑type instrument), frame drums, jaw harp, wooden flutes and whistles, fiddle, and later diatonic or button accordion. Circle and chain dances accompany many songs, emphasizing steady, grounded rhythms suited to communal movement.

Even as it absorbed neighboring Volga‑Ural influences, Mari folk music retained distinctive pagan ritual strata, audible in its invocatory refrains, responsorial textures, and trance‑supporting rhythmic cycles.

Mari folk music arose from the everyday life and spiritual practices of the Mari people. Before extensive documentation, songs marked the agricultural calendar, weddings, funerals, and communal gatherings, while ritual chanting and drumming accompanied nature‑focused pagan ceremonies.

The 1800s saw the first systematic collecting and notation of Mari melodies by ethnographers working across the Volga–Ural region. These collections captured heterophonic unison singing, modal contours, and the role of drones, and they documented instruments such as local zithers, flutes, and frame drums along with the growing presence of fiddle and accordion.

In the mid‑20th century, Mari folk repertoire entered formal state ensembles and cultural houses. While stage presentation standardized arrangements (adding choral parts and orchestrated folk‑instrument groups), collectors continued to record village singers and ritual specialists. Dance repertories and festival showcases preserved circle/chain dances and responsorial forms.

After the 1990s, local folklore ensembles, youth groups, and cultural festivals promoted language preservation and community performance. Field recordings and educational programs helped restore older ritual pieces and performance practice, while contemporary folk and folk‑rock acts occasionally re‑contextualized traditional melodies with modern instrumentation.

Mari folk music remains audible at festivals, village celebrations, and on professional stages in the Republic of Mari El and neighboring regions. Community choirs, instrumental ensembles, and ritual practitioners continue to transmit songs, dance rhythms, and performance techniques to new generations.

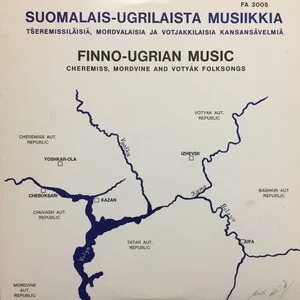

%20-%20Finno-Ugrian%20Music%20(Cheremiss%2C%20Mordvine%20and%20Voty%C3%A1k%20Folksongs)%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)

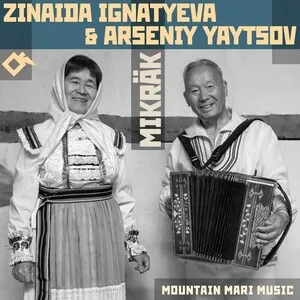

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)

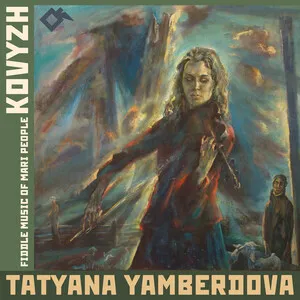

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)