Your digging level

Description

Uzbek music is a broad umbrella for the traditional, classical (maqom), folk, and popular styles of Uzbekistan. At its core lies the courtly shashmaqom tradition—a six-suite modal cycle (Buzruk, Rost, Navo, Dugoh, Segoh, Iroq)—alongside regional styles such as the Ferghana–Tashkent lyrical song (e.g., tanovar), the Khorezm maqom and the virtuosic Lazgi dance music.

The sound world is modal, melismatic, and predominantly monophonic or heterophonic rather than harmonically chordal. Melodies unfold within maqom modes using microtonal inflections and characteristic cadences, and are supported by cyclical rhythms (usul) on the doira frame drum. Core instruments include long-necked lutes (dutar, tanbur, sato), the bowed ghijak, end-blown nai, double-reed surnay, ceremonial karnay trumpet, and various percussions. Vocal traditions range from intimate ghazal settings to the powerful, group-projected Katta Ashula and epic dastan singing by bakhshi storytellers.

Over the 20th century, Uzbek estrada (popular song) and large ensembles blended these idioms with Western instruments and studio production, while post-independence scenes revived heritage performance practice and fostered globally minded fusions.

History

The roots of Uzbek music stretch back many centuries through Sogdian and Turco-Persian cultural layers. By the 18th century (1700s), the shashmaqom repertoire was codified in Bukhara’s courts, drawing on Persian/Tajik poetic forms and Islamic modal theory. Parallel regional practices flourished: Ferghana–Tashkent lyrical arts, Khorezm maqom and the animated Lazgi dance, and epic recitation (dastan) by bakhshi.

Long-necked lutes (dutar, tanbur, sato), the bowed ghijak, nai, surnay, karnay, and the doira frame drum formed core ensembles. Shashmaqom cycles interweave instrumental sections with vocal ghazals, emphasizing modal development, melisma, and cyclical usul rhythms. Knowledge passed via master–apprentice lineages and was embedded in social life—weddings, seasonal festivities (e.g., Navruz), and court ceremonies.

Urban centers like Tashkent, Samarkand, and Bukhara became hubs for professional ensembles. In the USSR, conservatories and state troupes documented and arranged folk and maqom materials. Figures such as Yunus Rajabi notated vast repertoires. Uzbek estrada emerged, and groups like Yalla popularized Uzbek melodies across the Soviet sphere while orchestration expanded with Western instruments.

After independence, cultural policy boosted heritage revival, regional schools, and instrument craftsmanship. Conservatory programs and festivals strengthened shashmaqom and regional styles, while international artists fused maqom modalities with jazz, ambient, and electronic textures. Contemporary pop thrives alongside traditional forms, and UNESCO inscriptions (e.g., shashmaqom, Lazgi) reinforced preservation and visibility.

How to make a track in this genre

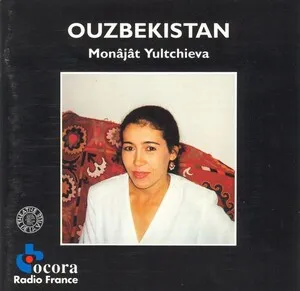

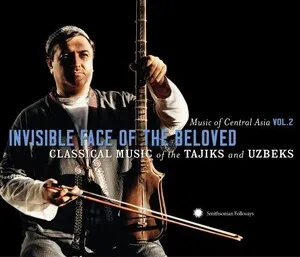

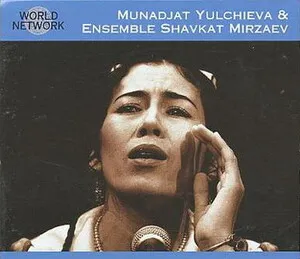

Top albums