Traditional raï is a folk-rooted vocal music from the Oran region of northwest Algeria. It emerged from Bedouin (bedoui) song forms and street poetry performed by cheikhs and cheikhas, using earthy vernacular lyrics to voice personal “opinions” (raï) about love, hardship, pleasure, and social taboos.

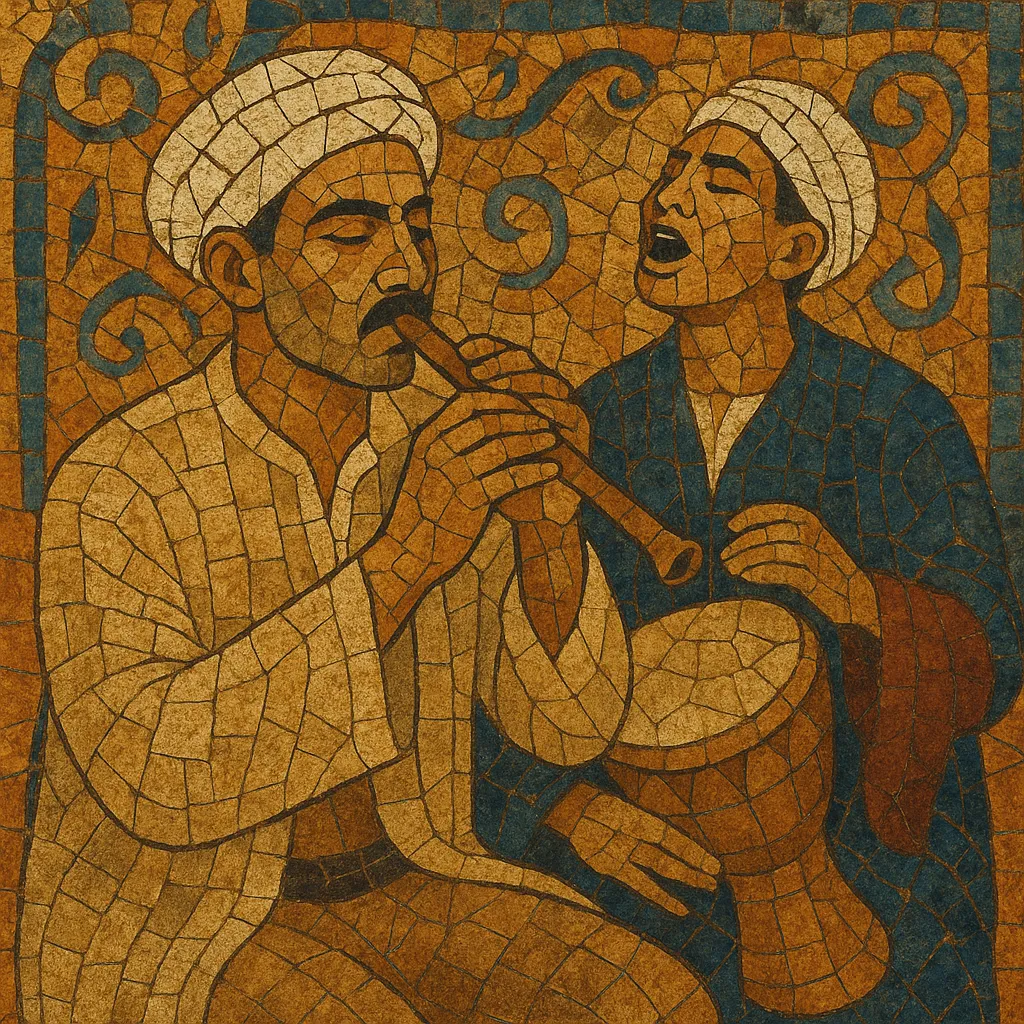

Musically, it centers on a raw, driving interplay between the gasba (end-blown reed flute) and the guellal (clay goblet drum), with highly ornamented, melismatic singing. Modal melodies draw on Maghrebi and wider Arabic traditions while keeping a direct, danceable pulse in 2/4 or lilting 6/8. The style is intimate yet exuberant—equally at home in cafés, weddings, and informal gatherings—and laid the foundation for later electrified and pop-inflected raï.

Traditional raï grew out of Bedouin musical-poetic practices around Oran (Wahrān), especially the sung verse and praise/banter traditions carried by cheikhs and cheikhas. It intersected with regional currents such as Maghrebi song, melhoun poetry, and the Andalusian-derived repertoire that nourished Algerian chaabi.

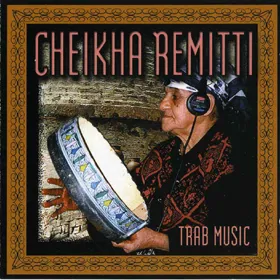

By the 1930s, a recognizable raï style coalesced in cafés, markets, and private festivities. Performers—often cheikhas—sang candid lyrics over gasba and guellal, projecting a distinctive vocal timbre full of ornamentation and grit. The word “raï” (meaning “opinion/advice”) reflected both the improvisational stance and the social directness of the texts. Early recordings on 78 rpm discs captured this raw sound and spread it beyond Oran.

Through the mid‑century, traditional raï remained largely acoustic and locally driven, prized for danceable grooves and unfiltered storytelling. Artists navigated shifting moral and political climates, sometimes facing censure for frank themes. Meanwhile, adjacent urban styles (notably chaabi) and changing instrumentation began to rub off.

In the 1970s, brass, electric instruments, and studio production steered raï toward modernization, but the core vocabulary—modal melodies, driving hand‑drum patterns, and frank vernacular poetry—remained the bedrock. This traditional base directly enabled the rise of modern and pop raï, which would carry the sound to international audiences.