Maghrebi music refers to the interconnected musical traditions of the western Arab world—primarily Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia (and to a degree Libya and Mauritania).

It blends Amazigh (Berber) indigenous music, Arab-Islamic modal practice, and the courtly Andalusi legacy brought from al‑Andalus after the medieval period.

Within this umbrella sit styles as diverse as Andalusi nūba suites, Algerian and Moroccan chaabi, Gnawa trance, Malouf in Tunisia, and popular forms like raï.

Typical features include maqam-based melody, cyclical hand-clapped and drum-driven rhythms (often in 6/8 and 2/4), heterophonic ensemble textures, call-and-response vocals, and languages ranging from Maghrebi Arabic (Darija) to Tamazight/Tachelhit and French.

Modern Maghrebi music also incorporates electric instruments, synthesizers, and global genres, creating hybrid sounds that retain a strong regional identity.

The musical identity of the Maghreb crystallized between the 11th and 15th centuries as Andalusi musicians and communities migrated from al‑Andalus to cities such as Fez, Tlemcen, and Tunis. Their courtly nūba (suite) traditions merged with long-standing Amazigh practices and Arab-Islamic liturgical and secular repertoires.

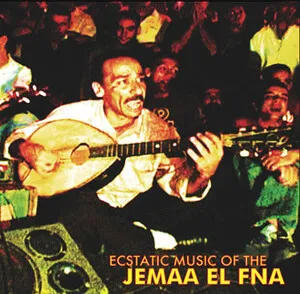

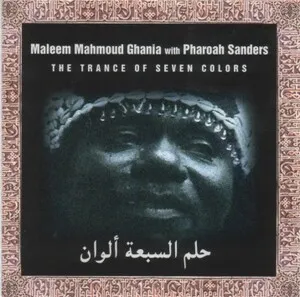

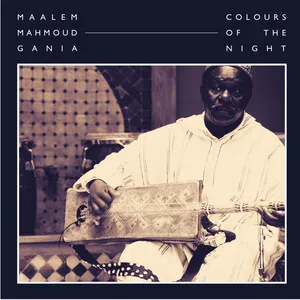

Alongside court music, Sufi brotherhoods nurtured devotional chant, ritual drumming, and trance practices. In Morocco, Gnawa ceremonies (lila) combined sub‑Saharan rhythmic logics with Maghrebi melodic language. Urban popular song—chaabi—developed in Algeria and Morocco with street-poetic lyrics, violins, ouds, and frame drums, while Tunisia maintained Andalusi-derived malouf.

French, Spanish, and Ottoman-era contacts brought new instruments (violin, accordion), performance contexts (cafés, salons, cabarets), and recording technologies. Early 20th‑century shellac records documented chaabi masters and Judeo‑Maghrebi singers, helping standardize local repertoires.

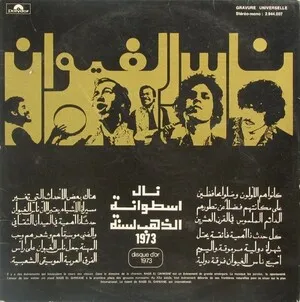

From the 1970s onward, electrification and migration shaped a new popular sound. In Algeria, raï modernized folk song with electric guitars, synths, and dance beats, reaching international audiences. Moroccan ensembles like Nass El Ghiwane renewed social poetry with polyrhythms and guembri/bendir textures. Diasporic scenes in France amplified Maghrebi styles and fostered fusions with rock, reggae, funk, and later hip hop and electronic music.

Today, Maghrebi music spans conservatory Andalusi orchestras, Sufi rituals, Gnawa-jazz fusions, and chart‑ready pop. Artists collaborate across Africa, Europe, and the Middle East, integrating maqam melody and Maghrebi rhythms with jazz harmony, club production, and global songwriting while preserving the region’s distinct timbres and modal aesthetics.