Your digging level

Description

Traditional maloya is the ceremonial and community music of Réunion, born among enslaved and indentured populations on the island. It blends East African and Malagasy rhythmic heritage with South Asian (notably Tamil) ritual elements, and is sung primarily in Réunion Creole.

The sound is anchored by hand-built percussion such as the deep, barrel-like roulèr drum, the constant shaker wash of the kayamb (a flat rattle made of sugarcane stalks and seeds), bamboo or stick drums like the pikèr, and the musical bow called the bobré/bobre. Vocals are typically call-and-response, dancing across cyclical grooves that can feel trance-like. Harmony is minimal; the power lies in interlocking rhythms, communal singing, and text delivery.

Historically linked to "servis kabaré" ancestor ceremonies and later to social protest and identity, maloya ranges from intimate a cappella and drum circles to larger ensembles that accompany dance. Its pulse is earthy and insistent, designed equally for ritual attention, communal healing, and collective movement.

History

Maloya took shape on Réunion in the 1700s and 1800s among enslaved Africans and Malagasy people on sugar plantations, later absorbing influences from South Asian (particularly Tamil) indentured workers. It drew on work song practices and ancestor-veneration rituals (servis kabaré), using locally crafted instruments such as the roulèr and kayamb to sustain communal singing and dance.

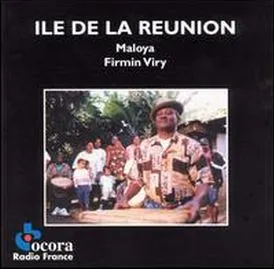

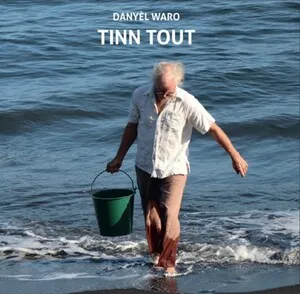

In the colonial and early post-colonial eras, public performance of maloya was discouraged or restricted, and it was often stigmatized as a music of the subaltern. Yet it persisted in private and ritual contexts. From the late 1960s through the 1970s, figures like Firmin Viry and later Danyèl Waro carried maloya back into public space, linking it to Creole identity, language, and social struggle. The genre became associated with protest movements and cultural revival on the island.

From the 1980s onward, traditional ensembles, women-led groups, and younger practitioners revitalized core practices—call-and-response singing, kayamb/roulèr-driven grooves, ritual poetics—while some artists experimented with electric instruments and studio production. In 2009, UNESCO inscribed maloya on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, cementing its status as a living tradition. Today, traditional maloya thrives in ceremonies, community gatherings, and staged concerts, and it continues to inspire modern offshoots such as electrified and electronic maloya.