Your digging level

Description

Pashto folk music is the traditional musical expression of the Pashtun people, centered in the mountainous regions of present-day Afghanistan and northwestern Pakistan. It is an oral, community-based tradition in which poetry and music are inseparable, celebrating love, honor (nang), homeland, tribal history, and everyday life.

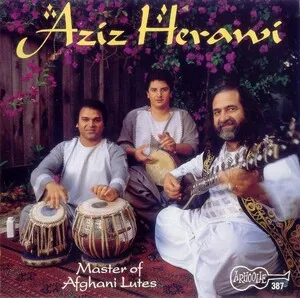

The sound is defined by the resonant, percussive timbre of the rubab (Afghan lute) and a battery of hand and frame drums—dhol, dholak, tabla, and zerbaghali—often joined by harmonium, surnai/shehnai (double-reed), and wooden flutes. Vocals are highly expressive and ornamented, moving within modal frameworks akin to regional maqam/dastgāh and Hindustani raga practice. Core folk forms include the ancient two-line tappa/landay couplet, narrative ballads (charbeta/badala), wedding and women’s songs, lullabies (neemakai), and dance music for the communal attan, which gradually accelerates to ecstatic intensity.

History

Pashto folk music emerges from centuries-old Pashtun poetic and communal practices. Forms like the tappa (often synonymous with landay, with its 9- and 13-syllable lines) are regarded as among the oldest Pashto verse, likely predating early modern Pashtun literature of figures such as Khushal Khan Khattak (17th century). Music functioned in village hujras (male community spaces), pastoral settings, tribal gatherings, and life-cycle ceremonies, with songs carrying genealogies, moral codes, and themes of love, bravery, and exile.

By the early modern period, the rubab had become the emblematic instrument across greater Khorasan and the Hindu Kush, anchoring Pashto folk ensembles with its resonant drone and brisk plucked textures. Over time, Hindustani classical (raga/taal), Persian modal aesthetics (dastgāh), and Sufi devotional practice intersected with local idioms, lending Pashto folk its melismatic vocalism, modal fluidity, and poetic spirituality. Double-reed surnai and powerful dhol rhythms underpinned public festivities and the attan dance, while harmonium and tabla from North Indian traditions supported ghazal-style renditions of Pashto poetry.

In the mid-20th century, broadcasting (notably Radio Kabul and later Radio Pakistan Peshawar) recorded and popularized folk artists, bringing rural repertories to urban audiences. The cassette boom of the 1970s–1990s further expanded circulation across bazaars and cross-border communities, even as conflict and displacement pushed performers and listeners into new hubs in Peshawar, Quetta, and the Afghan diaspora.

Periods of cultural restriction—especially during late-20th-century conflicts—curtailed public music-making, yet folk practice persisted in private gatherings and diaspora spaces. Women’s repertories and wedding music adapted to changing social conditions, and tappa/landay poetry continued as a living art of commentary and resistance.

Since the 2000s, studio productions, TV talent programs, and digital platforms have revitalized Pashto folk. Rubab-led ensembles and folk-pop crossovers have found new audiences, while the attan has become a powerful symbol of Pashtun identity worldwide. Collaborations with classical and world-fusion artists have placed Pashto melodies and rhythms on international stages without severing ties to village performance and oral transmission.