Your digging level

Description

Miejski folk (urban folk) is a Polish strand of folk music rooted in the songs, dances, and street-ballad traditions of big cities—above all interwar Warsaw. It draws on dance rhythms popular in city dance halls (tango, foxtrot, waltz, polka) and blends them with the narrative, often humorous or bittersweet storytelling of street singers.

Typical instrumentation includes accordion, guitar, banjo or mandolin, violin, double bass, and occasionally barrel-organ timbres, creating an acoustic but lively sound. Lyrics frequently use colloquial language, slang, or elements of Warsaw dialect and focus on everyday urban life: love, work, neighborhood camaraderie, and the city’s rough edges.

Contemporary revivals of miejski folk keep the core qualities—danceability, direct storytelling, and acoustic ensembles—while intersecting with singer‑songwriter, indie folk, and folk‑punk aesthetics.

History

Miejski folk traces its roots to the urban song and dance culture of interwar Poland, especially Warsaw in the 1920s–1930s. Street singers and courtyard bands popularized sentimental and humorous ballads alongside dance forms like tango, foxtrot, polka, and waltz. These songs captured the everyday experiences of city dwellers and helped define a distinctly urban strand of Polish folk.

After World War II, artists such as Stanisław Grzesiuk helped preserve the repertoire of Warsaw street songs, recording and performing pieces that might otherwise have disappeared. Courtyard bands (kapely podwórkowe) continued the tradition with accordion‑led ensembles and sing‑along choruses that kept the style audible in markets, festivals, and neighborhood events.

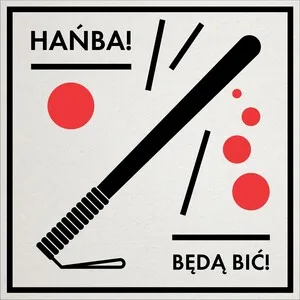

From the 1970s onward, groups like Kapela Czerniakowska maintained a living link to the classic repertoire. In the 2000s–2010s a fresh revival emerged: ensembles and singer‑songwriters reinterpreted urban folk with historically informed instrumentation, archival research, and modern production. Projects such as Warszawskie Combo Taneczne and new folk collectives re‑energized the style for stages and dance floors, while acts influenced by punk, indie, and cabaret aesthetics (e.g., Hańba!, Czesław Śpiewa) broadened its audience.

Contemporary miejski folk thrives at the crossroads of heritage and innovation. Artists mix archival songs with new originals, keep the dance pulse intact, and foreground storytelling that resonates with modern urban life. The result is a style that is both nostalgic and current—equally at home in folk festivals, city clubs, and community street events.

How to make a track in this genre

Use an acoustic, street‑band palette: accordion, guitar (or banjo/mandolin), violin, double bass, and light percussion (e.g., snare, woodblock, hand percussion). For period color, consider a small brass/clarinet part or a barrel‑organ/organetto timbre.

Base arrangements on social‑dance meters common to interwar city music: tango (4/4 with a habanera undercurrent), foxtrot (swing‑leaning 4/4), waltz (3/4), and polka (brisk 2/4). Keep tempos danceable and emphasize a steady, unpretentious pulse suitable for sing‑along choruses.

Favor diatonic progressions (I–IV–V, ii–V–I) with occasional borrowed chords or secondary dominants for a vintage feel. Melodies should be memorable and syllabic, allowing for clear storytelling. Use call‑and‑response or unison refrains to invite audience participation.

Write narrative, character‑driven verses about everyday urban life—work, love, neighborhoods, street humor, and bittersweet nostalgia. Employ colloquial phrasing or dialectal touches (e.g., elements of Warsaw slang) and balance humor with sentiment. Vocal delivery should be direct, warm, and slightly theatrical.