Your digging level

Description

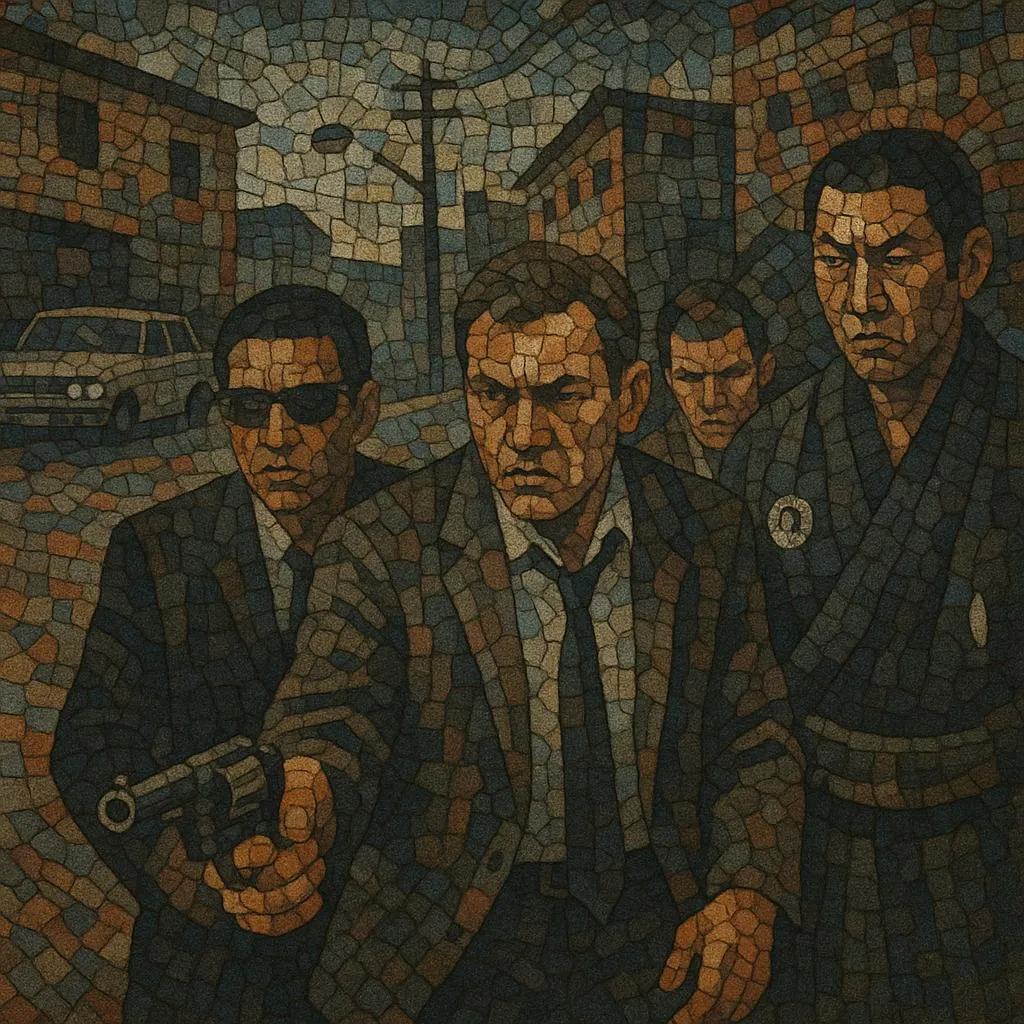

Jitsuroku eiga ("true record films") is a gritty strain of Japanese crime cinema that blossomed in the early–mid 1970s. Although fundamentally a film subgenre, it carries a distinct musical identity in its scores: lean, documentary‑like underscore punctuated by tough, streetwise cues.

Musically, jitsuroku eiga soundtracks fuse jazz and funk rhythm sections (dry drums, prominent bass, wah‑wah guitar) with sharp brass stabs, suspense strings, and occasional traditional colors (shakuhachi, taiko). Themes tend to be terse and motif‑driven rather than lushly melodic, reinforcing the genre’s semi‑documentary realism and moral ambiguity. The overall sound is tense, hard‑edged, and urban—ideal for chronicles of clan conflicts, police corruption, and post‑war social fracture.

Sources: Spotify, Wikipedia, Discogs, Rate Your Music, MusicBrainz, and other online sources

History

Jitsuroku eiga emerged in Japan in the early 1970s as a reaction against romanticized, chivalric yakuza pictures. Marketed as "true record" films, they drew on newspaper reportage and court testimonies to depict criminal organizations, police collusion, and post‑war black‑market realities with quasi‑documentary bite.

Japanese studios had already developed a rich crime‑cinema sound world: jazz combos, big‑band cues, and noirish harmony colored Nikkatsu action and Toei yakuza cycles. These idioms—along with TV newsreel textures—primed composers and music departments for a more austere, reportorial approach.

The breakthrough came with Toei’s landmark series such as Kinji Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honor and Humanity (1973–1974). Scoring shifted toward:

• Funk/jazz rhythm sections recorded dry and upfront • Brass and woodwind punctuations for stings and scene turns • Motif‑led themes that could be rapidly reprised between documentary‑style montage, voice‑over, and on‑screen captions • Sparing use of traditional timbres (e.g., shakuhachi) for local colorThis palette mirrored the genre’s handheld camerawork, fractured editing, and matter‑of‑fact narration.

As studios chased audience appetite for realism, composers refined a toolbox of chase grooves, tension ostinati, and grim, minor‑mode cues that could pivot quickly between police stations, alleyway ambushes, and boardroom betrayals. The music remained economical, favoring texture and rhythm over grand symphonic development.

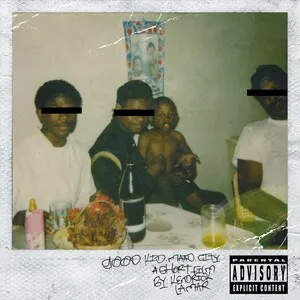

The jitsuroku aesthetic became a touchstone for later Japanese crime and neo‑noir works, and its taut jazz‑funk cues have been rediscovered by DJs and beat‑makers. In sample culture, 1970s Japanese crime scores are mined for dry drum breaks, gritty horn riffs, and suspense textures, feeding into strands of underground Japanese rap and boom‑bap production.