Javanese music refers to the courtly and vernacular musical traditions of the island of Java, Indonesia, centered historically in the royal courts of Yogyakarta and Surakarta. Its best-known expression is the gamelan ensemble, featuring tuned bronze percussion, voice, and soft winds/strings.

It is distinguished by two tuning systems—sléndro (five-tone) and pélog (seven-tone)—organized into pathet (modal frameworks) and articulated by colotomic cycles marked by gongs. A skeletal melody (balungan) is elaborated by interlocking parts (cengkok and sekaran), creating a shimmering, stratified texture. Vocal music (tembang macapat, sindhenan) and ceremonial genres coexist with dance, theater (wayang kulit), and ritual contexts.

Aesthetic ideals value refinement (alus), balance, and subtlety, with flexible tempo layers (irama) and nuanced dynamics. The result ranges from tranquil and meditative to majestic and processional, supporting everything from royal rites to popular song forms like langgam Jawa and campursari.

Javanese musical practice predates written records, with bronze ensembles and ritual song embedded in Hindu–Buddhist courts (Majapahit) and village life. The modern court idiom—its repertories, ensemble types, modal (pathet) theory, and ceremonial functions—was consolidated in the 18th century within the Mataram successor courts of Surakarta and Yogyakarta. Distinct tuning systems (sléndro, pélog), colotomic cycles, and genre forms (ladrang, ketawang, lancaran) were formalized alongside wayang kulit and court dance.

Under Dutch colonial rule, court culture continued while new urban styles emerged. Portuguese-influenced kroncong and later popular salon idioms interacted with Javanese aesthetics. Notation systems such as kepatihan (cipher notation) spread in the late 19th–early 20th centuries, aiding pedagogy and preservation. Court master musicians trained generations of performers and composers, shaping regional variants (Surakarta vs. Yogyakarta).

Following Indonesian independence (1945), Javanese music was embraced as national heritage. Conservatories and radio broadened access; composers experimented with form, extending irama, texture, and orchestration while maintaining pathet logic. New hybrids like langgam Jawa and, later, campursari fused gamelan with guitar, keyboard, and dangdut rhythms, bringing Javanese language and melodic sensibility to mass audiences.

From the late 20th century, Javanese gamelan ensembles spread worldwide ("American gamelan"), influencing Western minimalism and experimental music. Today, court ensembles remain active; community groups animate village rituals; and artists continue to innovate—writing new works, collaborating across genres, and integrating electronics—while preserving the core aesthetics of balance, modal nuance, and cyclical time.

Use a Javanese gamelan ensemble as your core palette: metallophones (saron, demung, peking), knobbed gongs (gong ageng, kempul, kenong, kethuk, kempyang), bonang (barrel gongs), gender, gambang (xylophone), and soft-sounding elaborators such as rebab (two-string spike fiddle) and suling (end-blown flute). Add voice: a female soloist (pesindhen) and a male chorus (gerong). Kendhang (drums) lead tempo and cue transitions.

Choose a laras (tuning system)—sléndro (5-tone) or pélog (7-tone)—and a pathet (modal framework) that governs final tones, cadences, and typical melodic curves. Build your piece within a colotomic cycle (gongan) using forms like lancaran (short, lively), ladrang (medium), or ketawang (lyrical). Mark structural points with kenong and end cycles with the gong ageng.

Write a balungan (skeletal melody) in kepatihan cipher notation (1–7 numbers). Layer elaborating parts: bonang and gender weave cengkok (stock patterns), gambang and rebab ornament the line, and the pesindhen floats freely above, resolving to modal tones. Maintain irama relationships (tempo-density layers) so that as the pulse slows, elaborating densities increase proportionally.

Let kendhang patterns shape character: kendhang ciblon for dance-like, lively pieces; kendhang kalih for dignified or processional moods. Cue changes in irama, section repeats, and cadences with drum signals and breath-like tempo rubato at cadential points.

For vocal works, set macapat poetic meters (e.g., Dhandhanggula, Kinanthi) in Javanese language. Align phrase endings with pathet cadences. Write sindhenan (solo) lines that glide ornamentally, while gerong supports with syllabic refrains that track the balungan.

Aim for alus (refined) balance: avoid abrupt contrasts, favor smooth timbral blends, and let large cycles breathe. Introduce soft–loud (alus–gagah) sections by shifting instrument cohorts rather than extreme dynamic spikes. End sections with clear gong punctuation and tasteful ritardando into the final strike.

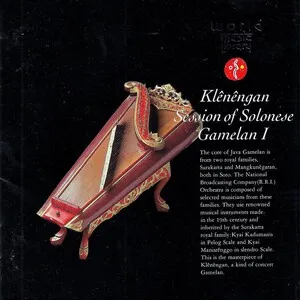

%20Orchestra%20-%20Kl%C3%AAn%C3%AAngan%20Session%20of%20Solonese%20Gam%C3%AAlan%20I%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)