Free jazz is a radical branch of jazz that rejects fixed chord progressions, strict meter, and conventional song forms in favor of collective improvisation, textural exploration, and spontaneous interaction. Musicians prioritize timbre, dynamics, and gesture as much as pitch and harmony, often using extended techniques (multiphonics, overblowing, prepared piano) and unconventional sounds.

While rooted in the blues and earlier jazz vocabularies, free jazz frees improvisers from pre-set harmonic cycles, allowing lines to unfold over tonal centers, shifting modes, drones, or complete atonality. Rhythm sections may float without a steady pulse, or drive with layered polyrhythms and “energy playing.” The result ranges from contemplative soundscapes to cathartic, high-intensity eruptions.

Culturally, the genre intersected with the civil rights era and broader avant-garde movements, emphasizing autonomy, community, and new possibilities for musical expression.

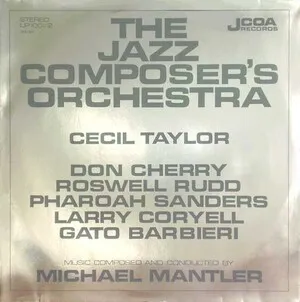

Free jazz emerged in the United States at the end of the 1950s as musicians sought to transcend bebop’s harmonic density and hard bop’s codified language. Pianist Cecil Taylor and saxophonist Ornette Coleman were pivotal: Taylor’s early recordings pushed form and rhythm toward abstraction, while Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come (1959) and Free Jazz (1960) proposed collective improvisation unfettered by fixed chord changes. These experiments drew from the blues, gospel/spirituals, modal approaches, and contemporary classical ideas (Third Stream), reframing jazz as an open system rather than a style with preset rules.

The early 1960s saw a wave of innovators: John Coltrane’s classic quartet moved from modal frameworks into intensely exploratory late works; Albert Ayler introduced raw timbres, wide vibrato, and folk-like themes detonated by free improvisation; Archie Shepp fused political urgency with extended forms; Sun Ra developed cosmic big-band freedom with electronics and theater. This ferment coincided with the civil rights movement, and many musicians framed artistic freedom as social and political expression. Independent labels and New York loft spaces provided crucial infrastructure for this music.

In the 1970s, free jazz intertwined with the Chicago-based AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians), spawning the Art Ensemble of Chicago and boundary-crossing composers like Anthony Braxton. In Europe, players such as Peter Brötzmann, Evan Parker, and Derek Bailey pushed toward free improvisation scenes distinct from (but indebted to) American free jazz. The music seeped into rock, progressive forms, and experimental traditions, influencing no wave, progressive rock, and later noise scenes.

The ‘loft jazz’ generation matured into a durable ecosystem of festivals, small labels, and academic programs. Free jazz practices informed spiritual jazz revivals, modern creative currents, and cross-genre collaborations (from jazz fusion to post-rock and avant-metal). While aesthetics range from quiet, textural minimalism to ferocious energy music, the core remains: collective listening, structural openness, and sound-as-composition.