Field hollers are solo, unaccompanied vocal cries historically performed by African Americans in the rural U.S. South, especially in plantations, levee camps, railroad gangs, and prison farms. They were used to communicate across distances, express emotion, keep time, or relieve the isolation of field labor.

Musically, hollers feature elastic, free rhythm; soaring melismas; blue notes; wide glissandi; sudden dynamic shifts; and improvised text. Singers often project at high volume, using falsetto, moans, whoops, and bends to carry over long distances. While mostly solo, hollers sometimes prompted distant call-and-response with other workers.

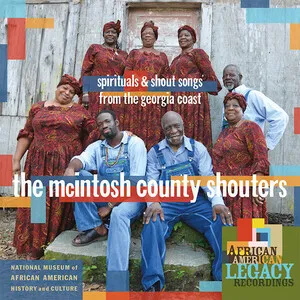

Lyrically, field hollers range from short location calls or work-time signals to longer complaint songs and personal laments, touching on separation, longing, hardship, and news. The style is a foundational ancestor of the blues and a close cousin to ring shouts and spirituals, preserving core elements of West African vocality within oppressive working conditions.

Field hollers emerged among enslaved Africans and their descendants in the American South during the 1800s (with roots likely extending into the late 1700s). As a functional vocal practice in plantation fields and other labor settings, the holler drew deeply from West African vocal aesthetics—free rhythm, melisma, improvisation, and expressive timbre—adapted to the acoustic and social realities of forced labor.

Unlike group work songs that keep collective rhythm, the field holler is typically a solo cry. It could signal information (time of day, location), convey feelings (pain, longing), or simply project a presence across distance. Its flexible meter, sliding intonation, and powerful projection made it ideal for open fields, levees, and camps.

After Emancipation, hollers persisted in levee and railroad camps and on sharecropped land. Their melodic contours, “blue” inflections, and vocal rhetoric strongly informed early country blues and Delta blues singing, where the voice remained elastic over a sparse guitar accompaniment. Holler techniques also colored the delivery of spirituals and later gospel.

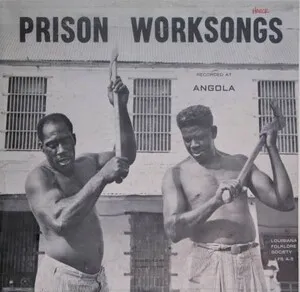

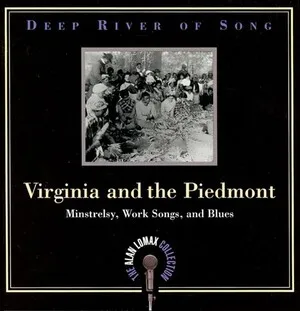

Early commercial recording seldom captured pure hollers, but folklorists such as John and Alan Lomax documented them in the 1930s–1950s (notably at Mississippi’s Parchman Farm and Texas prison farms). Industrialization, urban migration, and changing labor patterns reduced the need for long-distance vocal signaling, and the practice waned. Today, field hollers live on through archival recordings and as an acknowledged cornerstone of the blues and broader American vernacular music.

The field holler’s vocal grammar—blue notes, microtonal slides, improvisation, and emotive intensity—became fundamental to blues, influenced gospel delivery, and even left traces in country yodeling and later popular styles that prize expressive, flexible vocal lines.