Your digging level

Description

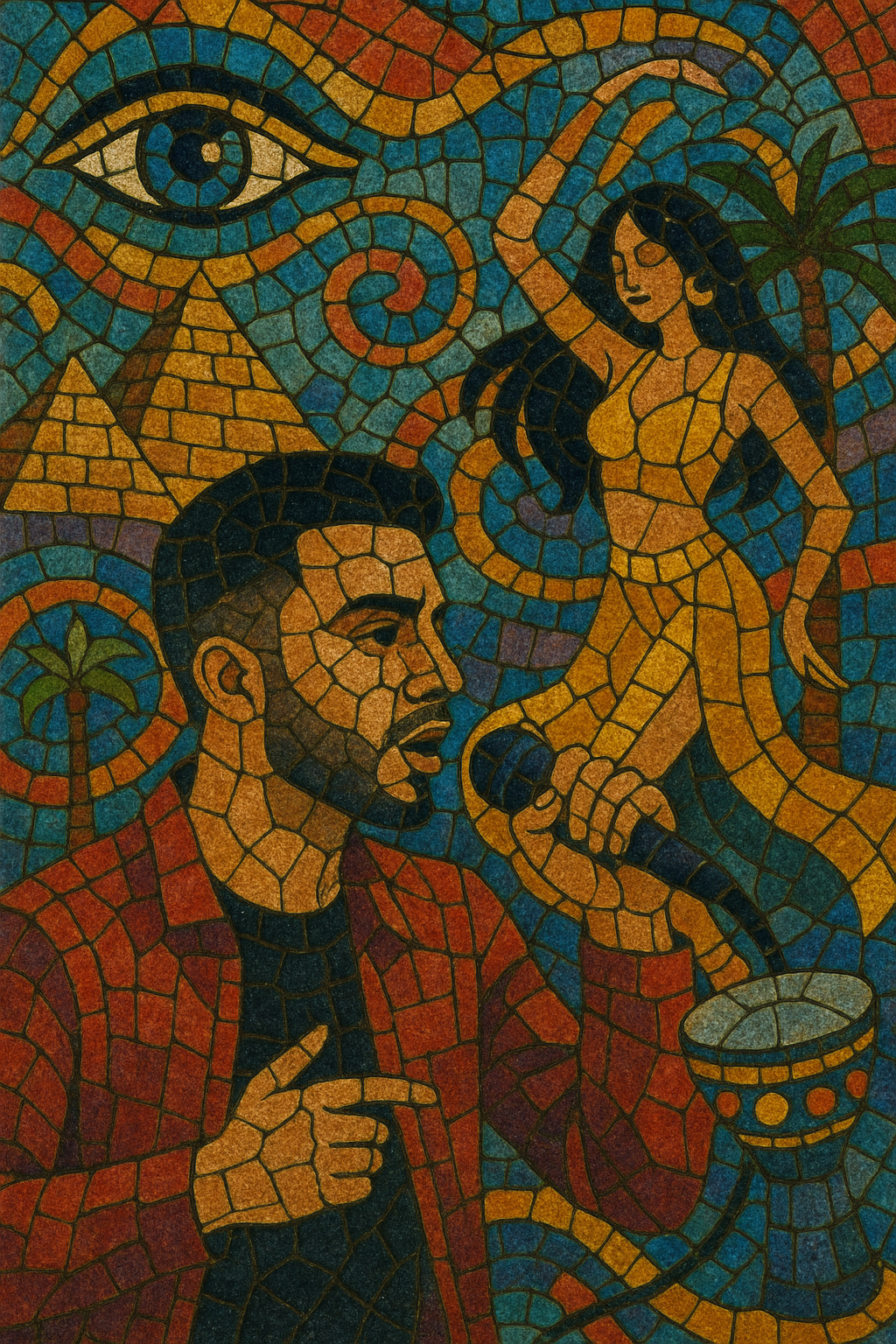

Egyptian viral pop is contemporary Egyptian pop designed for rapid spread on social platforms, especially YouTube, Instagram Reels, and TikTok.

It blends mainstream Egyptian pop songwriting with street-level shaabi/mahraganat grooves and modern hip hop, trap, and EDM production. Songs are short, hook-first, and built around chantable refrains, memeable catchphrases, and danceable beats. Vocals are often in colloquial Egyptian Arabic with generous use of Auto‑Tune, while arrangement choices highlight a 15–30 second snippet optimized for short‑form video.

Typical productions fuse darbuka and riqq percussion with 808s, claps, bright synth leads, and occasional mizmar, sax, or oud motifs. The overall effect is energetic, catchy, and built to travel quickly across the MENA region and diasporic audiences.

Sources: Spotify, Wikipedia, Discogs, Rate Your Music, MusicBrainz, and other online sources

History

Egyptian viral pop grew out of the existing Egyptian pop industry as audiences shifted to YouTube and streaming. Established stars began prioritizing singles and video-first releases, while a wave of street-informed sounds—shaabi and, later, mahraganat—introduced punchier rhythms and colloquial delivery. By the mid‑2010s, tracks were already being written with shareability in mind, culminating in region‑wide hits such as “3 Daqat” (2017) that proved how quickly a catchy Egyptian pop song could spread online.

The TikTok era supercharged the format. Producers emphasized ultra‑memorable chorus lines, rhythmic drops, and short intros so that the most infectious 15–30 seconds could be clipped. Mahraganat’s street pulse and rap’s 808‑driven low end blended with pop toplines, yielding viral smashes like “Bent El Geran,” which transcended local scenes and charted globally. At the same time, pop‑rap crossovers and celebrity‑driven singles (e.g., high‑profile collaborations) broadened the style’s reach.

As the sound dominated charts and feeds, it sparked debates about taste, censorship, and the line between mahraganat, rap, and mainstream pop. The Musicians Syndicate’s public scrutiny of certain lyrics and performers drew attention, yet online momentum continued to drive discovery, with artists leveraging dance challenges, influencer tie‑ins, and soundtrack placements.

Egyptian viral pop remains a distribution‑driven, hook‑first approach more than a rigid musical category. The core toolkit—colloquial hooks, maqsoum/baladi‑flavored grooves, trap/EDM production sheen, and video‑centric storytelling—continues to define how Egyptian hits break across the MENA region and diaspora.