Your digging level

Description

Early American folk refers to the traditional songs, dance tunes, ballads, hymns, and work songs that circulated in the North American colonies and the young United States from the 18th through the mid-19th century.

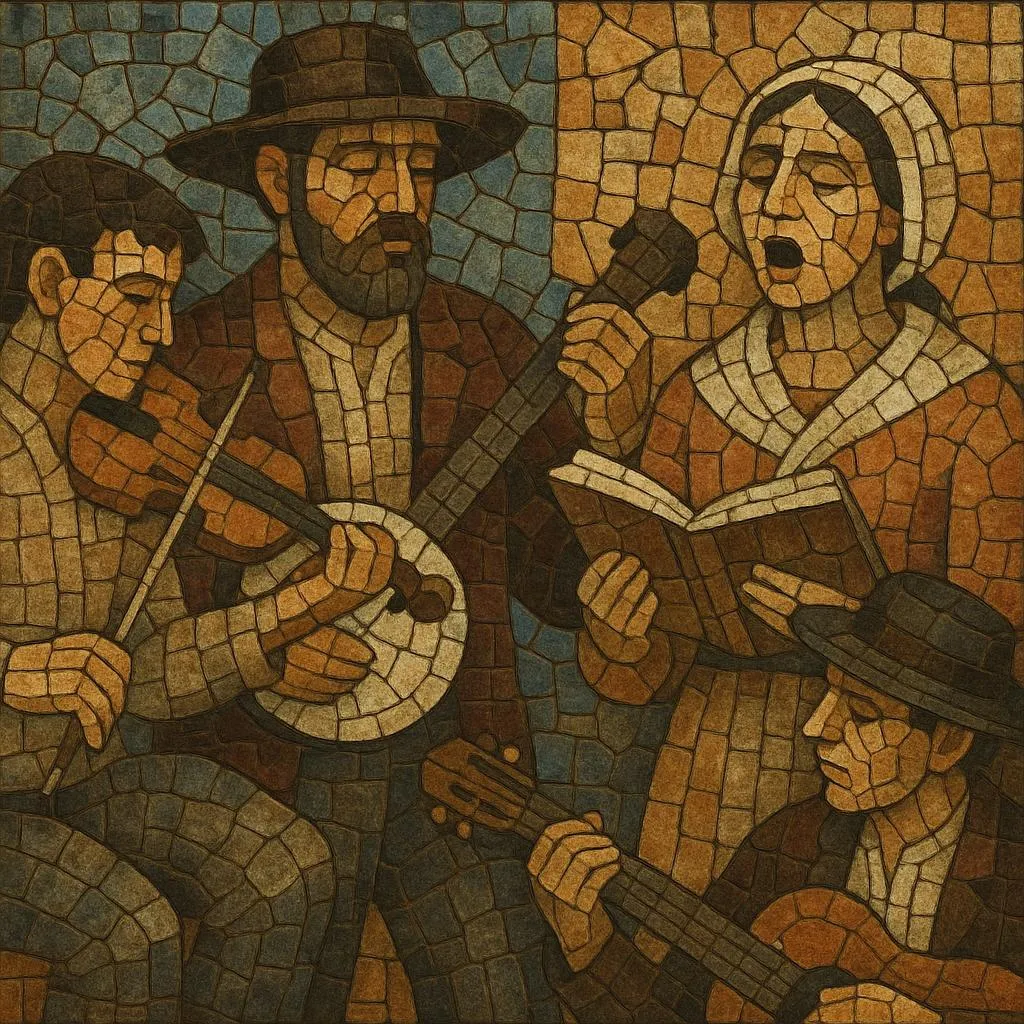

The repertoire blends ballad and dance tune traditions from the British Isles with African-American rhythmic practices and instruments (notably the banjo), Indigenous North American melodies and ceremonial song structures, and European sacred singing (psalmody and later shape‑note/Sacred Harp). Much of it was transmitted orally, with local variants emerging region by region. Typical sounds include unaccompanied ballad singing, fiddle-and-fife dance bands, fife-and-drum corps, dulcimer and banjo string music, and robust congregational hymn-singing.

History

Early American folk took shape as settlers in the colonies brought English, Scottish, and Irish ballads and dance tunes (reels, jigs, hornpipes), which mingled with Indigenous musical practices and the musical cultures of enslaved Africans. Congregational psalm-singing and later frontier camp-meeting hymns added a powerful sacred strand. Many pieces were transmitted orally, spawning local variants and regional styles.

During the American Revolution and early republic, fife-and-drum corps, march tunes, and broadside ballads circulated widely, while country-dance fiddle music animated social gatherings. Shape-note tunebooks and community singing schools flourished in New England and Appalachia, codifying a distinctive, open-voiced choral sound in sacred folk repertoire (the Sacred Harp tradition).

By the early–mid 1800s, parlor song and printed broadsides coexisted with older ballads and dance music. African-American influence deepened the rhythmic vocabulary and instrumentation (banjo, bones, call-and-response), while sea shanties, canal and railroad work songs, cowboy songs, and frontier fiddle music broadened the repertoire. Regional traditions (New England hymnody, Appalachian ballads, Southern string-band music, and fife-and-drum lines) developed strong local identities.

Although much of this music remained community-based, collectors and later folklorists documented the tradition from the late 19th into the 20th century. Its vocabulary and repertoire became the foundation for old-time, country, bluegrass, and the 20th‑century American folk revival, while Sacred Harp and shape-note singing continued as living communal practices.