Your digging level

Description

Corridos clásicos are the traditional, narrative ballads of Mexico that crystalized during the Mexican Revolution and the mid‑20th‑century recording era. They tell true‑to‑life stories of heroes, outlaws, love, border crossings, working people, and tragic events.

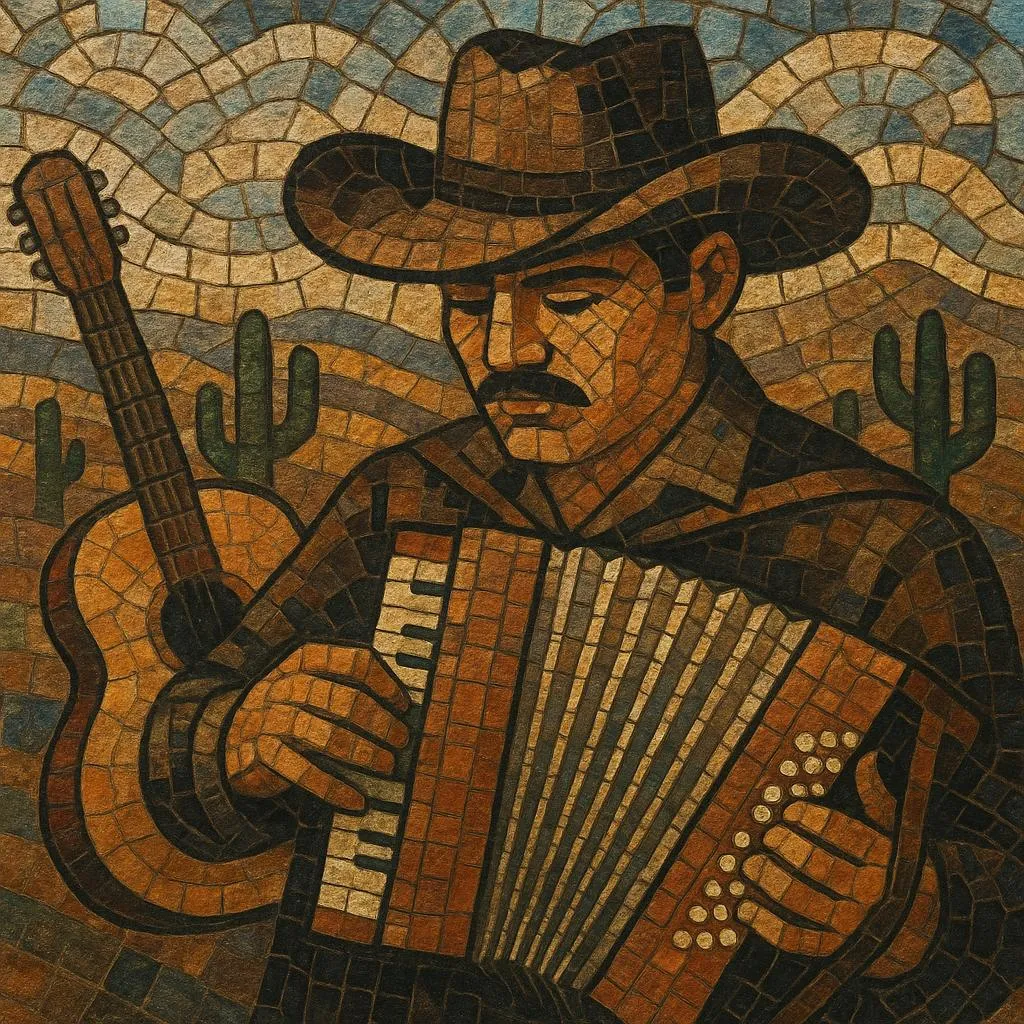

Musically, classic corridos are strophic songs sung in a declamatory, story‑forward style over dance rhythms borrowed from European forms—chiefly polka (2/4) and waltz (3/4). Harmonies are straightforward (I–IV–V in major keys), and melodies are memorable but subordinate to the text. Typical ensembles include guitar and bajo sexto with accordion in norteño settings, or full brass and percussion when performed by banda sinaloense; mariachi groups also keep many classic corridos in their repertoire.

Compared with later narcocorridos or corridos tumbados, corridos clásicos retain acoustic instrumentation, an older poetic craft (octosyllabic lines and assonant rhyme), and an emphasis on historical or communal storytelling rather than glamorizing crime or fusing trap/urban production.

History

The corrido’s literary roots lie in the Spanish romance (ballad) and in Mexican oral poetry. By the late 1800s, narrative songs about local events, injustices, and folk heroes were common along the Mexican North and borderlands. During the Mexican Revolution (1910s), the form flourished as a popular news medium, carrying accounts of battles, leaders, and everyday lives to audiences with limited access to print media.

Radio, 78‑rpm discs, and later LPs helped stabilize the musical profile of the corrido: strophic verses over polka or waltz accompaniments in major keys, with clear, narrative vocals. Mariachi, early norteño duets, and regional brass bands (banda sinaloense) recorded large catalogs, elevating iconic stories (of revolutionaries, horse races, and tragedies) into a shared canon. This repertoire and performance style are what later came to be called corridos clásicos.

Norteño groups with accordion and bajo sexto—alongside Sinaloan brass bandas—popularized corridos nationwide and among the Mexican diaspora in the U.S. Acts standardized instrumental breaks, intros, and codas while preserving narrative clarity. Thematically, songs covered border life, labor, and community heroes, maintaining the sober, reportorial ethos of the classic tradition.

From the late 1980s onward, narcocorridos and later fusions (urban/trap‑inflected corridos) branched from the tradition. As these newer styles grew, audiences and curators began labeling the earlier narrative, acoustic, and historically minded repertoire as corridos clásicos to distinguish it from contemporary subgenres.

Digital archives, reissue labels, and streaming playlists have revived interest in classic corridos. Bands and soloists continue to perform them in norteño, banda, and mariachi formats, while modern songwriters study their poetic craft (octosyllabic lines, assonant rhyme, saludo/despedida) to write new songs in the classic mold.