Your digging level

Description

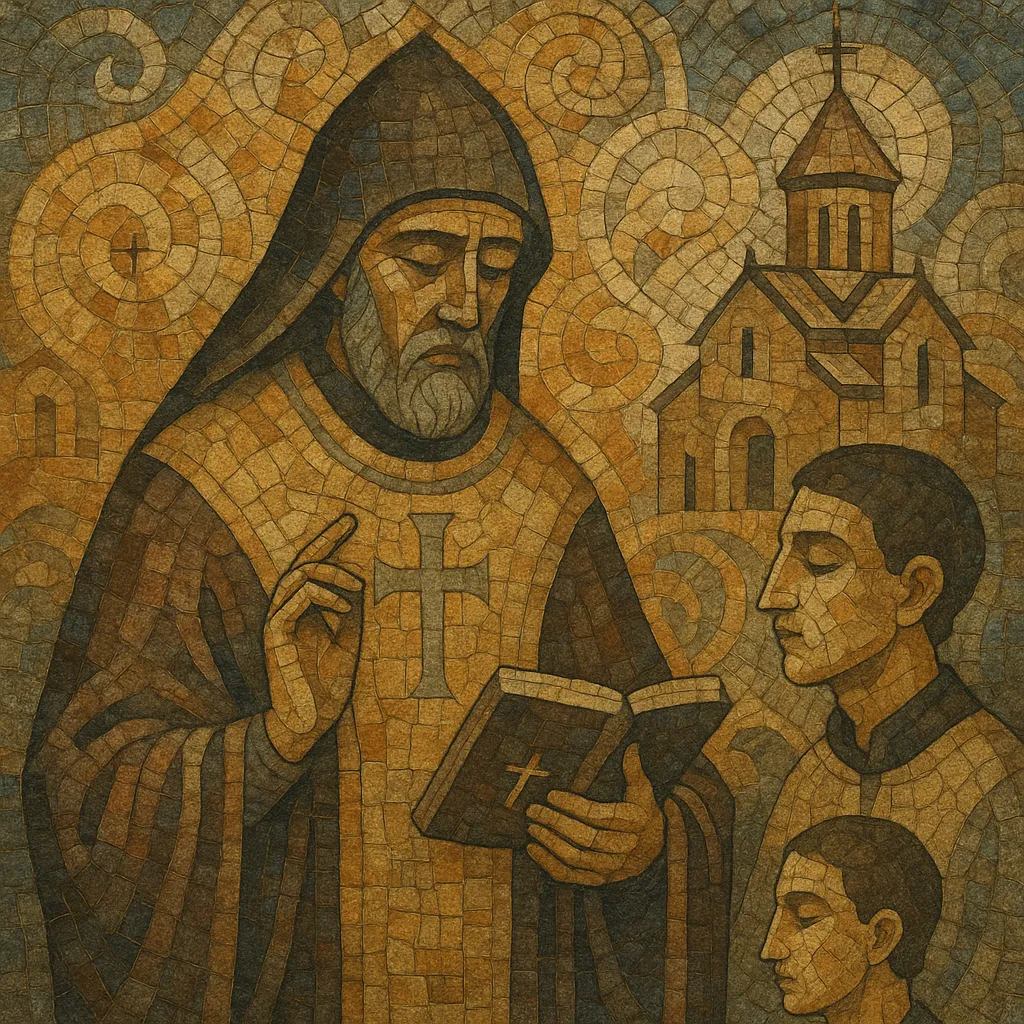

Armenian church music is the sacred chant and liturgical repertoire of the Armenian Apostolic Church, sung primarily in Classical Armenian (Grabar) and preserved through oral transmission, medieval neumatic (khaz) notation, and later staff transcriptions. It centers on the Divine Liturgy (Badarak), the daily offices, and a vast corpus of hymns known as sharakans.

Musically, the tradition is fundamentally monophonic and modal, drawing on an eight-mode (oktoechos) system with characteristically stepwise melodies, narrow to moderate ambitus, and expressive melismas. While the historical tradition is a cappella and unaccompanied, modern choral harmonizations (notably by Makar Yekmalyan and Komitas Vardapet) are also widely performed, carefully respecting the modal flavor of the original chants. The sound is solemn, luminous, and contemplative, with an emphasis on textual clarity, rhetorical pacing, and devotional atmosphere.

History

Armenia adopted Christianity in 301 CE, and a distinct sacred musical practice emerged soon after. The creation of the Armenian alphabet by Mesrop Mashtots (c. 405) enabled the flourishing of hymnography and the systematic compilation of texts for the liturgy. Early chant was transmitted aurally by clergy and monastic singers.

Between the 8th and 10th centuries, the khaz neumatic notation developed to record melodic contours, ornaments, and performance practice. Although the precise decoding of all neumes remains complex, the system reflects a sophisticated modal practice related to the broader Near Eastern and Eastern Christian oktoechos. The tradition privileges monophony, rhetorical pacing, and an oratorical, prayerful delivery.

Medieval Armenia saw a golden age of hymnography and theological poetry. Figures such as Grigor Narekatsi and Nerses Shnorhali enriched the sharakan repertory with texts of profound spiritual and poetic depth. Monastic centers and cathedrals (e.g., Etchmiadzin) cultivated learned chant traditions and treatises (e.g., by Stepanos Syunetsi) that codified practice.

In the 19th century, Makar Yekmalyan composed a polyphonic setting of the Divine Liturgy that became a touchstone of modern performance. Komitas Vardapet (Soghomon Soghomonian), priest and ethnomusicologist, collected, transcribed, and critically edited chants, seeking to restore authentic modal intonation and declamation while creating sensitive choral realizations. During the Soviet period, sacred practice was constrained, but choirs in Armenia and the diaspora (Istanbul, Jerusalem, Tiflis, New Julfa, and beyond) preserved the tradition.

Today, Armenian church music is sung worldwide by parish choirs and professional ensembles. Scholarly projects and choirs continue to study khaz notation, refine modal intonation, and revive lesser-known sharakans, ensuring the continuity of this ancient, living tradition.

How to make a track in this genre

Top albums